Kentucky had been a state for ten years when the Judiciary Act of 1802 reorganized the federal court system. Together with a local district court judge, each justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (there were then six) was tasked with hearing cases in one of the nation’s six circuits. The justices heartily disliked “circuit riding” for legal reasons, but also because of the difficulties of early nineteenth-century travel. In fact, so intolerably distant were the judicial districts of Kentucky, Tennessee, Maine, and the territories that the Act did not even include them in any of its circuits. Not until 1807 did a newly created Seventh Circuit comprise Kentucky and its fellow outliers, Tennessee and Ohio.

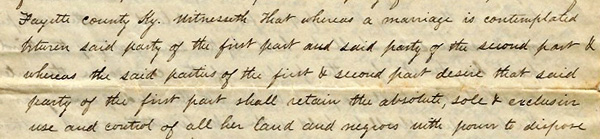

Meanwhile, recognizing that its district courts were overloaded, Kentucky enacted legislation in 1802 establishing its own circuit court system. Some circuits were comprised of more than one county, but Warren County alone made up the Warren Circuit. Convening on the first Monday in March, June and September, the court succeeded to the powers of the old district and quarter-sessions courts, and had trial jurisdiction over both civil and criminal matters except those involving less than five pounds in money or one thousand pounds of tobacco.

But amidst all the administrative details of establishing the new courts, one was overlooked. In 1804, recognizing that “each of the circuit courts of this commonwealth should possess a seal of office, and no provision hath heretofore been made for that purpose,” the General Assembly directed each court to procure a seal for not more than ten dollars, to be paid out of the money collected from fines and costs.

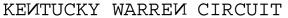

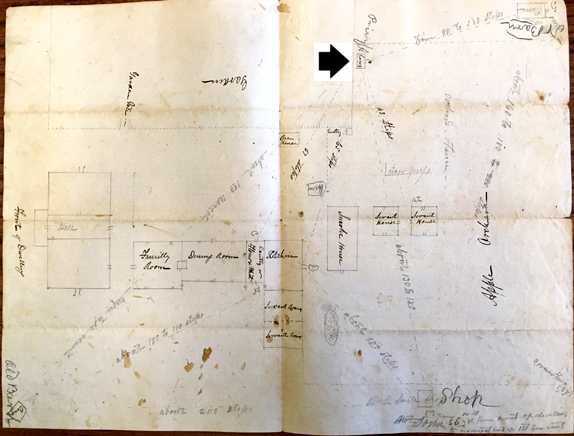

A few early court records in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library bear this seal. In a design reminiscent of the Great Seal, the center shows a bald eagle bearing in its talons an olive branch and arrows. Encircling the eagle are the words:

Oh dear. What happened? Do we have a mistake resembling the “Inverted Jenny,” the 1918 U.S. postage stamp showing an airplane upside down? Did the engraver become confused, thinking the “N” had to be reversed in order to appear correctly when the seal was applied? Or do we just have an unschooled engraver trying to extrapolate the appearance of the uppercase letter from a lowercase “n”? Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century gravestones sometimes bore reversed letters – “s” and “z,” in particular, as well as “n” – but an official seal?

In any event, the backwards “N” doesn’t seem to have bothered anyone, perhaps because another ten dollars would have been required to fix it. The seal stayed in use until at least 1839. By 1860, another seal carried the correct lettering, together with a more pastoral image in the center. We see that one in use until at least 1902.

Click here to access more information about locating these seals, along with a little history on Warren County’s early courts and the subjects of some early indictments. Click here for a finding aid to some of our early court records. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.