Bowling Green native Dorothy Grider (1915-2012) wasn’t even out of high school before she began summer studies at the Phoenix Art Institute in New York. To earn a scholarship to the Institute after her freshman year at WKU, she submitted a portrait of “Pete,” a local African-American man known for his expertise with foxhounds. Today, it’s in the collections of the Kentucky Museum at WKU.

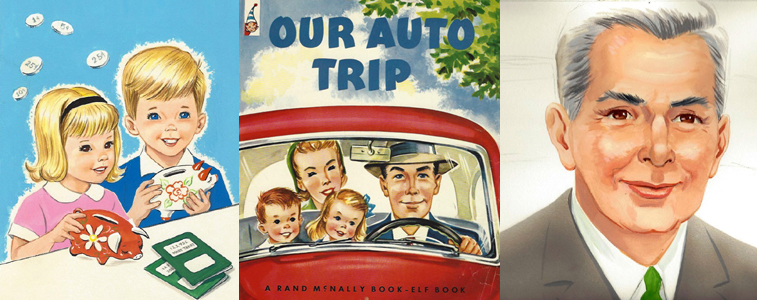

Grider would go on to enjoy decades of success as a commercial illustrator, especially of activity, coloring and story books for children. She had a long relationship with the publisher Rand McNally, which featured her work in some of its most popular titles. Not only did her drawings of adorable puppies, bunnies and kittens delight children, her rendering of an earth mover in the story The Busy Bulldozer earned kudos from an employee of the Caterpillar Tractor Company.

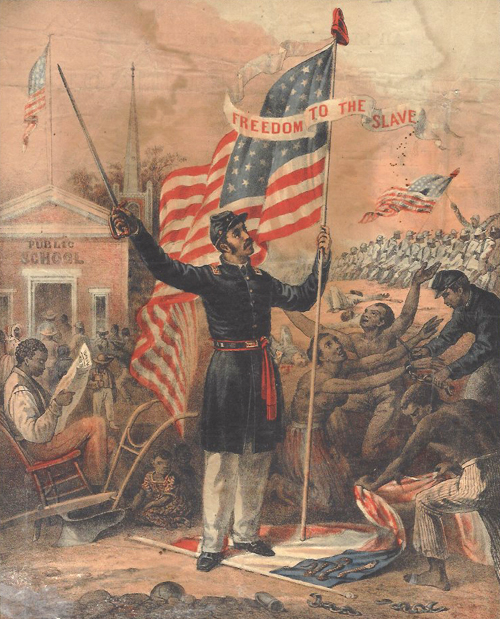

When it came to children’s books, however, Grider’s artistic license was necessarily more circumscribed, subject not only to the commercial exigencies of the day but to the cultural assumptions and prejudices of the 1950s. Grider’s drawings for books like Our Auto Trip invariably featured children and families that were nuclear, middle-class, and almost incandescently white. Editorial scrutiny of artwork that strayed from this baseline was unforgiving. “PLEASE MISS GRIDER,” Rand McNally implored after an examination of The Busy Bulldozer, “WILL YOU SEE TO IT THAT YOUR SKIN TONES THROUGHOUT THIS BOOK ARE CLEAN-LOOKING AND LIGHT?” Once “heavied up” by the lithographer, “skins with this dark a cast” ended up looking—well, non-Caucasian.

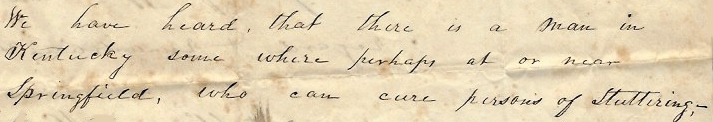

Other content besides skin color worried Family Films of Hollywood, which vetted Grider’s drawings for a filmstrip called We Go to Church with an eye to the sensibilities of its religious audience. “In order to please some of the denominations who take a dim view of stimulants,” the editor suggested removing a coffee pot from the family breakfast table and replacing the parents’ cups of coffee with cocoa. Similarly, the “little white gloves” worn by the young daughter were “real cute and stylish,” but perhaps “a little too ‘sophisticated’” for attendance at an average church kindergarten.

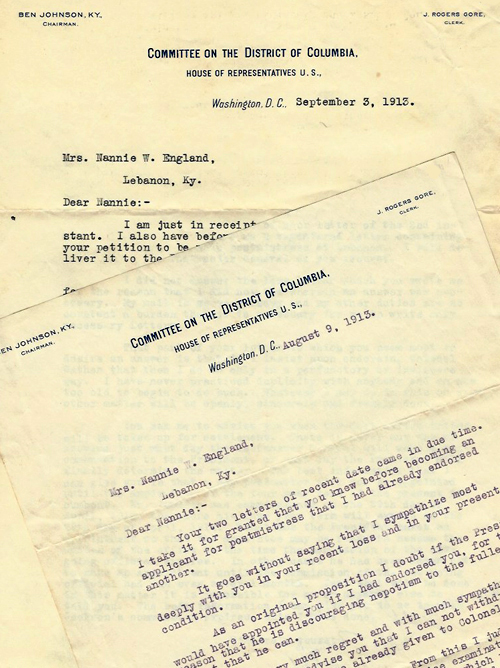

By 1970, however, the “D-word” (diversity) was creeping into Rand McNally’s thinking. The company sent Grider a script for Hoppity Skip, a new addition to its Start-Right Elf educational series, and asked if she’d be interested in the work. “We’d like a sprinkling of the other races introduced,” were its rather timid instructions, “perhaps a Negro, Oriental, Puerto Rican. . . .” The dam was breaking, but Grider’s work nevertheless remained subject to the formula that makes all such creatives pull out their hair: an editor’s message of fulsome praise, followed by the dreaded words “I have only a few suggestions. . . .”

Dorothy Grider’s papers and artwork are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives collections of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. To see more of our holdings of her books and artwork, search KenCat.