Oh, to be a college sophomore—a term said to derive from the Greek “sophos” and “moros,” literally, a “wise fool.” You have survived your lowly freshman year, made some friends, learned your way around, and returned to campus convinced that you own the place.

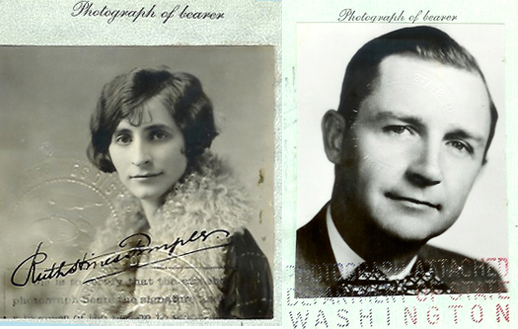

Long before she became head of WKU’s Art Department, Bowling Green’s Ruth Hines Temple enjoyed this enviable position when she arrived at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College in September 1920. In a letter to her “Dearest Darling Mother,” she excitedly reported on her financial, material, social, and—oh yes—academic preoccupations as she began her second year.

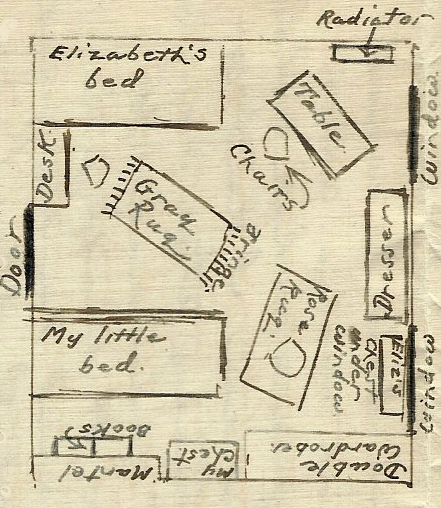

First on the list was the furnishing of her dormitory room. Using funds from a drugget (a no-frills floor covering) bought during her freshman year, then sold (albeit at a discount), she and her roommate had purchased some blue curtains and a gray wool rug that, together with a rose-colored rug, looked “just divine.” The place needed some prettying up, for Ruth had found herself domiciled on the second floor of Main Hall, the oldest building on campus. Her room had a fireplace that was now blocked up, but no worries: she and her roommate had placed their bookshelves in front of “the hole,” and enjoyed having the mantel as “another place to put things.” They had removed the back from a washstand and converted it into a desk, and covered their chair backs with cretonne (a heavy cloth used for upholstery). Other aspects of Main Hall were more problematic, as the venerable building had been expanded over the years to accommodate some public uses. Ruth’s room was right next to an auditorium-style chapel, so she would have to watch herself during those times when entertainments were in session and “I will want to sally forth in my kimono.”

Ruth’s academic plans for the year were eclectic but showed her tacking toward artistic pursuits. She had used her “star” status in Freshman English to insist that “girls who could write should certainly be given an opportunity to do it,” and thereby squeezed her way into a course on exposition and short story writing. Though she had succeeded in enrolling in an interior decoration course, she was somewhat disappointed that an art professor could not take her on as an assistant—“with all my talent”—until she had a degree.

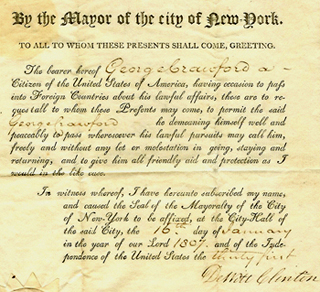

But the first weeks of sophomore life weren’t complete without a little “stunt” or two at the expense of the freshmen. While soliciting subscriptions for the college newspaper, a classmate had come up with a way to more quickly enhance the second-year class coffers. “Have you paid your radiator tax yet?” Ruth and her mates would ask the freshmen, who would “run and get their pocket books and fork it over.” Some were relieved of a dime, others a quarter, but, Ruth chortled, all was fair. “We just gave the Freshmen the experience in exchange for the money”—not to mention a scheme they could adopt next year as “wise fools” themselves.

Ruth Hines Temple’s letter to her mother is part of the Temple Family Collection in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.