Many considered George Owen Barnes (1827-1908), a native of Paintsville, Kentucky, one of America’s premier evangelists of the late-nineteenth century. His message was strictly non-denominational and was targeted to a more charismatic audience that believed in faith healing. His father, a Presbyterian minister for fifty years, made sure George received a good education: Centre College and Princeton University. Prior to beginning a church ministry, Barnes and his wife served as Presbyterian missionaries to India for seven years. Afterwards he held pastorates in Danville and Chicago. In February 1882 Barnes and his equally talented wife, Marie, visited Bowling Green for a protracted meeting.

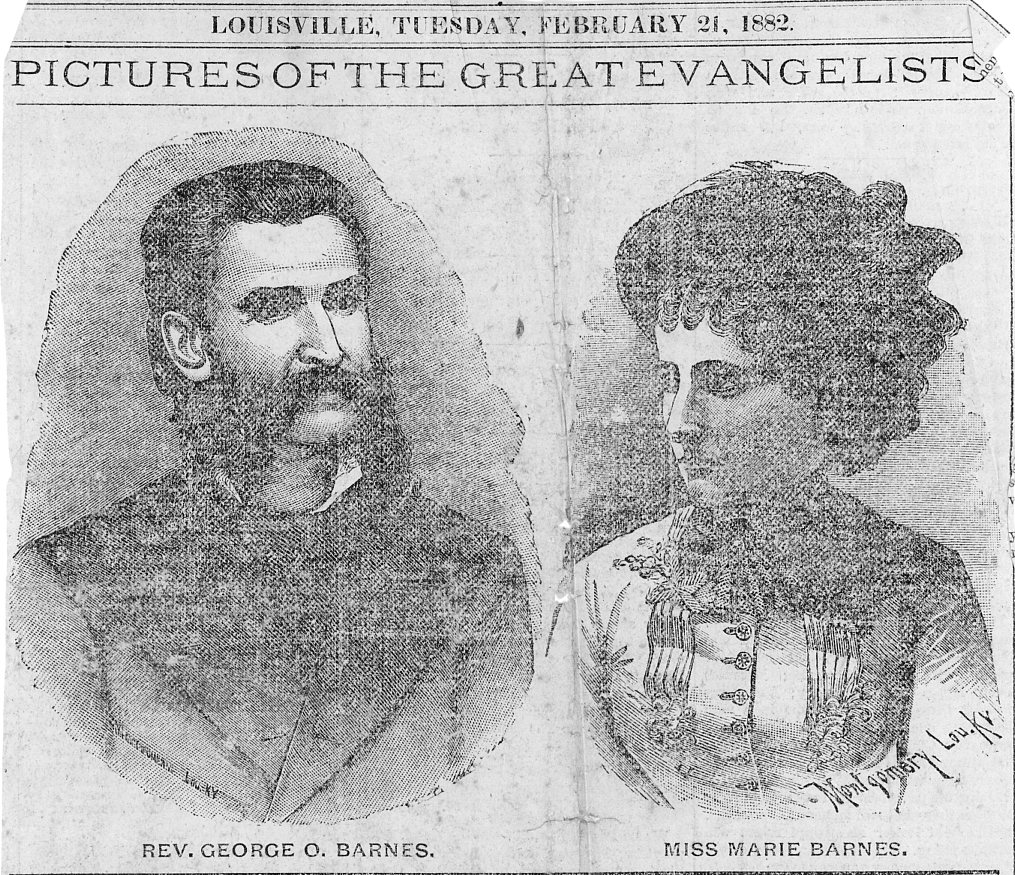

Reverend Barnes’s name came up recently, when Library Special Collections was allowed to copy a small collection of items removed from a family Bible. The items included a long clipping from an unnamed Louisville newspaper dated February 21, 1882. The main title was “About Barnes” but the clipping boasted a number of odd subtitles, i.e. “Pen and Ink Drawings of Two Persons Who Draw Better Than the Siamese Twins” and “Their Wonderful Seven Weeks’ Work in a City Full of Sinners.” This was all fine, until we discovered from the last subtitle “A Bowling Green Preacher’s Welcome” that the “city full of sinners” was Bowling Green, Kentucky.

The lengthy article is almost exclusively biographical and a large portion of it is missing. Fortunately Library Special Collections owns Barnes’ massive published journal titled Without Scrip or Purse, or The Mountain Evangelist, George O. Barnes: This History of a Consecrated Life, the Record of Its Silent Thoughts, and a Book of Its Public Utterances. In it we learn about the protracted meeting Barnes held in our fair city. The Bowling Green entries begin with the overall numbers from the meetings: “771 for the soul and 421 for the body”—referring to 771 “saved” souls during the meeting and 421 healed bodies. The report notes that the downtown Methodist Church hosted the first service on 21 February with about 150 present. The size of the crowd warranted moving it to the larger Baptist Church the following day. Six local ministers attended and endorsed the meetings. The following day while taking a hike to the boat landing, Barnes noted regrettably that the city had “twenty-five licensed saloons…a fearful array against our Lord.”

By the weekend, numbers swelled and organizers moved the meetings to Odeon Hall (the Opera House). On one day alone, February 26, 115 people were “saved.” Despite the soul and body cures, Barnes tried to remain humble. “I want my faith,” he opined, “to rest on the Word of the Lord, and not on success. That only a cup of refreshment.” Throughout the period Barnes worked in town, he took prolonged walks visiting the sick of soul and body. He often frequented the homes of African Americans. It was clear that his meetings were ecumenical and that he did not tolerate racial prejudice.

As he left Bowling Green on March 8, Barnes noted in his journal: “Left Bowling Green…rain pouring and almost a hurricane raging. Satan seemed, in spite, to be blowing us out of his stronghold, where in seventeen short days our Jesus had struck him so many deadly blows.”