With the growth of the temperance movement in the late 19th century came a tide of programs for the treatment of addiction, not just to alcohol but to tobacco and drugs. Some were faith driven, but others were from the medical community and became so popular that they evolved into business franchises. One of these was the Hagey Institute, an enterprise that made an appearance in Bowling Green in the 1890s.

Only a few years earlier, in 1889, William Henry Harrison Hagey, a physician and chemist, had opened the first institute in Norfolk, Nebraska. Like several other aspiring addiction specialists, he touted bichloride of gold, a remedy that would supposedly eliminate the craving for alcohol and tobacco and for drugs like morphine and opium. Patients drank a tonic and also received injections of the compound which, it was said, left a gold stain on the upper arm. Hagey Institutes soon opened in California and as far away as Australia.

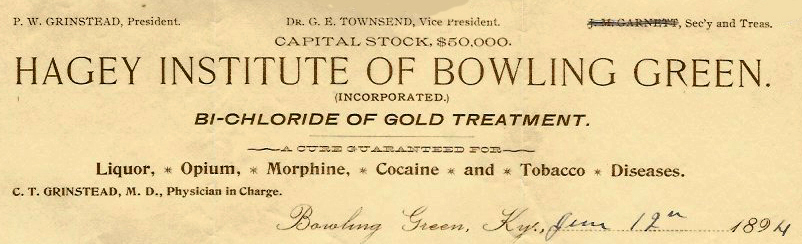

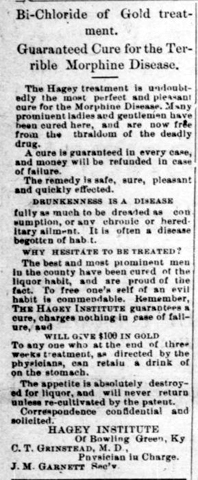

Bowling Green’s Hagey Institute was established no later than July 1892, when the Todd County Progress advised those “addicted to the liquor or morphine habit” to seek a cure there. The principals were local pharmacist Gilson E. Townsend and Glasgow’s Dr. Charles T. Grinstead (“Physician in Charge”). An advertisement assured patients of a “guaranteed” solution for “the Terrible Morphine Disease.” As for the “liquor habit,” the Institute did not sermonize; like drug addiction, it was a disease rather than a moral failing, “fully as much to be dreaded as consumption, or any chronic or hereditary ailment.” The ad further offered “$100 in gold” to anyone who, at the end of three weeks of treatment, confounded the cure by managing to keep down a drink of liquor.

Although the Hagey treatment promised to be “perfect and pleasant,” these gold-based regimens soon fell out of favor. It came as no surprise, perhaps, that laboratory tests showed the secret formula for the elixir to contain not gold but practically everything else, including quinine, strychnine and other poisons, and even alcohol, morphine and opium! Rather than instituting a pleasant withdrawal, it more commonly made users nauseous, fatigued, inebriated, confused, and even “insane.” But as the shadow of quackery began to advance over the gold cure, there is no evidence that Grinstead and Townsend’s enterprise was operating under less than good faith. Townsend later served twice as mayor of Bowling Green, and Dr. Grinstead deployed the Institute’s impressive gold-tinted letterhead to support Barren County physician John B. White in his attempts to defend himself against the “tattlers and liars” attacking his competence.

Dr. Grinstead’s letters from the Hagey Institute of Bowling Green can be found in the Jones Collection, part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more of our collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.