From William Coolidge’s 1822 journey to New Orleans to Josiah Ware’s 1837 Ohio River odyssey, the perils of nineteenth-century travel by water are well represented in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives collections of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Here’s another incident featuring Keturah “Catherine” Ward of Newport, Kentucky and husband Charles, whose journey to a new life in Georgia took a wrong turn off the coast of North Carolina in 1836.

Charles Ward’s children and thirty-six-year-old wife had followed him through military postings in Delaware, New York and Vermont. Returning to his family at Fort Hamilton, New York after service in the Second Creek War, Charles, to Catherine’s surprise, resigned from the Army. Increasingly unhappy with the military’s disruption of his family life, he had decided to relocate to Marion County, Georgia and try his luck in a mercantile partnership.

On October 8, 1836, the Wards left New York aboard the William Gibbons, a packet steamer carrying 140 passengers. Its captain, recently called out of retirement, was happy to leave command in the hands of the first mate and navigator—a careless choice at the best of times that would, under the conditions of this voyage, prove disastrous.

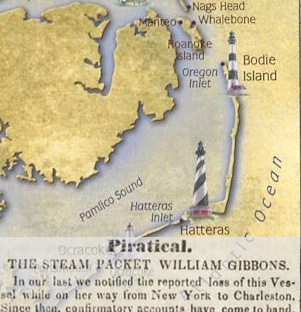

Visibility was poor the next night when, spotting Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, the ship turned west to round the Cape toward deeper water. Unfortunately, the lighthouse was not at Cape Hatteras, but at Bodie Island some 50 miles to the north, and the ship was now on a collision course with North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Early in the morning of October 10, she ran aground.

Most of the passengers—116, according to later accounts—were ferried to land, but without their baggage. They were deposited in two abandoned houses while the rest of the passengers stayed aboard to ride out an approaching storm. Catherine described the conditions on shore in a letter to her sister. Since the trip began, everyone had been “very seasick” and unable to eat, and the failure of the captain to deliver provisions extended their time without food to some four days. The only victuals came courtesy of an unlucky “small sheep” captured nearby, “cooked and divided into one hundred and sixteen parts.”

After the storm, the feckless captain finally came ashore to help, and the Wards obtained respite in Norfolk, Virginia. The crew, however, was even less heroic. Fortified with liquor, they had proceeded to cut open the baggage left behind on the William Gibbons, taking money, jewelry and clothing, and even rifling through the mail bags on board. “While we were on shore,” wrote Catherine, “our trunks were broken open and robbed mine had all my spoons and tumblers in it but were at the bottom and [the plunderers] were satisfied with taking my gold watch. We suffered no little I assure you.” Miraculously, no lives were lost in the wreck, but husband Charles estimated that he was “a loser by it to the amount of between three and five hundred dollars.”

Charles and Catherine Ward’s letters about the William Gibbons wreck are part of the Sumpter Family Collection. Click here for a finding aid. For more collections, search TopScholar and KenCat.