A recent donation to the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library offers a glimpse of the complex family affairs of the Thomsons of Fayette County, Kentucky, including the legal position of women in this well-off and propertied family.

In 1849, Sarah Thomson, a widow of 48, decided to marry Samuel Salyers, a farmer almost 20 years her junior. Sarah’s first husband had bequeathed her several hundred acres of land and 28 enslaved persons – all of which, under the laws of Kentucky, would become her new husband’s property in exchange for his obligation (real or imagined) to support her. Even if the couple had disowned this state of affairs by agreeing that “what’s mine is mine, what’s yours is yours,” the law could still operate, for example, by seizing Sarah’s assets to satisfy Samuel’s debts, by nullifying a contract entered into by Sarah under her own name, or by ignoring her attempt to devise her property by will.

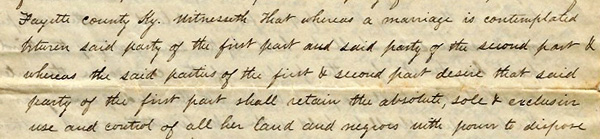

The workaround – as wealthier and better-informed families knew – was for the woman first to divest herself of legal title to her property by conveying it to a trustee, who would hold it for her use and benefit free of the claims of her husband-to-be. Accordingly, Sarah, Samuel, and Sarah’s son Patrick Henry Thomson signed a deed of trust appointing Patrick as trustee. The document acknowledged the status of Sarah’s acreage as a working farm, obligating her to consult with Patrick on the cutting of timber and sale of enslaved persons, but otherwise made clear that her control of the property, including the right to devise by will, was to be “absolute, sole & exclusive.”

As some of our other collections show, these marriage contracts could do the job they were intended to do, or precipitate litigation when the messy business of marriage economics intervened. In 1836, Ann and Samuel Winder had simply agreed in their contract that Ann could, at any time after their marriage, elect to have a trustee hold her property separate from her husband’s. When she exercised the option seven years later by nominating her son-in-law, her husband raised no objections, and the Warren County Court held that that their contract to agree on a trustee later was valid and binding.

Things were rockier in 1845, when Ruth Wheeler appealed to the same court to complain that her husband William had ignored their contract and that her trustee had failed to stand up for her rights. William, she charged, had dealt with her property as if it was his own, selling assets, using funds to buy an enslaved young boy, and collecting notes and rents in his name rather than in the name of Ruth’s trustee. When she proposed selecting another trustee, William had become “excited, irritable & unkind,” suggesting some collusion between the two. For his part, William took a position more commonly associated with a wronged wife: his personal services throughout their marriage, he claimed – building a “comfortable brick dwelling” on Ruth’s farm, supervising their enslaved labor, and managing income and expenses – had all gone unappreciated and uncompensated. He denied Ruth’s claims that his treatment of her had forced her to abandon their home, but also denied that “by entering into said marriage contract” he had intended to make himself “a slave.” Fortunately for his case, William produced receipts, and the parties settled on an amount for his services, ending the litigation – and presumably, their cohabitation.

Click on the links to access finding aids for these materials on marriage contracts. For more of our collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.