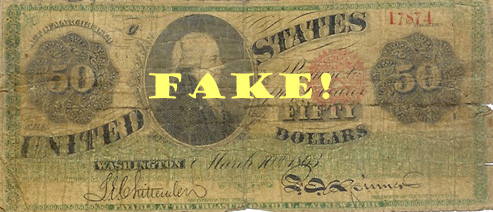

It was 1872, and Baker Smith was in trouble. The 40-year-old African American distillery worker had just been indicted by the Warren Circuit Court for passing a counterfeit $50 U.S. Treasury note. Smith had used the note to pay for 10 cents worth of dry goods, but Bowling Green bankers Potter & Vivion had refused to accept it from the merchant. Witnesses testified that after the note was returned to him, Smith attempted to pass it to another creditor.

At trial, the jury was instructed that, in order to find Smith guilty, they had to determine whether he knew the note was a fake and intended to represent it as genuine. The evidence was conflicting: one witness testified that although the front of the note was better than the back, the counterfeiter had done a good job; another, however, pronounced the counterfeit a poor one.

In his defence, the illiterate Smith was able to claim a fair amount of due diligence. After his emancipation from slavery, he had continued to work for his former owner (also named Smith) and had asked him to confirm that the note was genuine. For good measure, he had also asked two other local men who professed to be “experts” on money, and they agreed with owner Smith that the note was good. But now, these and other witnesses on whom Smith sought to rely had mysteriously disappeared, leaving him to plead with the court to suspend the trial until they could be located.

Although we may never know Smith’s fate, this and several other counterfeiting cases from the 1870s are part of a large collection of Warren County court cases being processed in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives section of WKU’s Special Collections Library. For further information, contact us at mssfa@wku.edu. For more about our collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.