“Some things I’ve seen here I [wouldn’t] believe if I hadn’t seem them.” So declared an awestruck soldier on finding himself in Louisville, Kentucky, for military training at Camp Zachary Taylor.

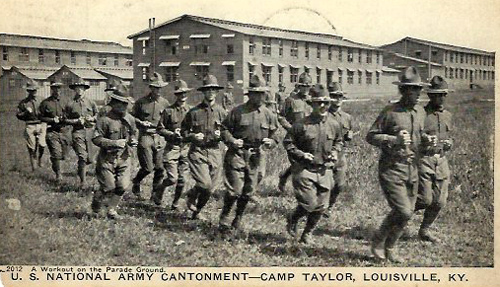

After the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, Camp Taylor (named for the U.S. president and former Louisville resident) materialized in a mere 90 days. The largest of 16 such camps across the country, it grew to the size of a small city, with more than 2,000 buildings and a population of as many as 47,000 troops. As they passed through the camp, soldiers wrote to family and friends with their impressions, and the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections holds many such letters.

Some noted the rigors of their training. “We hiked about three miles with all of our equipment,” wrote “Mack” Muncy, “and I have been tired ever since.” Arthur Miller, an enlistee from Connecticut, complained of “the nervous tension” resulting from a three-month crash course in artillery. But other aspects of military life drew more frequent comment as young men were ushered into a new world of routine and regimentation. Part of their “processing” ordeal was receiving vaccinations, which left many of them light-headed, sore-armed and sick. Of his two shots, Wilson Sprowl wrote “that first Doce [dose] made some [of] the Boys sick and some fa[i]nted.” Several of his mates, confirmed Grant Sorgen, “laid down from the vaccination, but I got thru O.K.” Contagious illness, nevertheless, plagued this large group of assembled humanity from all parts of the country. Fay Alexander found himself part of a quarantine “because one of the fellows got awake with the measels.” Jim Grinstead had already had measles, but was worried that if too many of his fellow soldiers fell ill, “they will keep all of us in and that will give me hell” for “I have a date with my girl.”

Other aspects of camp life were more satisfying. From most accounts, the food was tasty and plentiful. “This morning we had coffee, biscuits, fried potatoes, cream of wheat and bacon,” wrote Fay Alexander. “They sure do eat up the grub.” Grant Sorgen was happy with “a fine shower bath to-day and three good meals. So far, ‘This is the life,’” he declared, “but may not last long.” Just as memorable was the hospitality of the local citizenry. Arthur Miller enjoyed regular Saturday entertainment at the “Hawaiian Gardens” dance hall, courtesy of “numerous, sweet and innocent southern maidens.” Mack Muncy concurred: “Yes the girls are pretty free with us boys it is no trouble to get acquainted down here; if a fellow hasn’t got a girl it is his fault I am shure.”

On September 9, 1918, Private Ivan Wilson arrived at Camp Taylor. Wilson, who would go on to a long teaching career in WKU’s art department, was a diminutive 5 feet 4-1/2 inches and just over 100 pounds. Nevertheless, the gentle Calloway County native resolved to meet the challenge. Though consigned to clerical duties, he found the Army “thrilling”: “When I really did get my uniform on,” he wrote in his diary, “I knew that Germany would soon surrender.” And Germany did. On February 24, 1919, Wilson was discharged from Camp Taylor a “150% better man than when I came. I am going back into civilian life much better prepared to face the issues of life: to pass things which formerly have depressed me and has caused me to pine my life away in vain.”

Click on the links to access finding aids for these collections. In this centennial year of the U.S.’s entry into World War I, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat for more of our war collections.