I am agreeably surprised that of all the members of the house I have not seen a man who was drunk and only three or four who looked like they had drunk any. If this continues it will be remarkable and will be a credit to the body.

When he arrived in Frankfort in January 1914 to take his seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives, J. Guthrie Coke found this and other reasons to be optimistic. Following three earlier generations of his family into public office, the 47-year-old Logan County banker and farmer had resolved to “place one rule for measurement against all things and that is is it right.”

In letters—he called them “journals”—addressed to his wife Carrie, Coke took careful note of his surroundings—Frankfort was “a pretty town” but the magnificence of the Capitol made its houses look drab by comparison—and tried to understand the peculiarities of the democratic body of which he was a member. On the positive side, he found himself “favored far more than any new man has been” with assignments to seven committees. He enjoyed making the acquaintance of his fellow legislators and resolved to learn all their names. On the negative side, Coke found some of his colleagues “trying in their several and limited capacity to do good,” others paralyzed as they contemplated “the effect of each thing they do upon their constituents,” and still others consumed as much by “some trivial measure as upon one of great moment” purely on the grounds of principle. And then there were the pesky lobbyists for the school book publishers and the railroads; the latter, he wrote, “are the worst . . . they flood the legislature both Senate and house and give every executive officer we have all the passes they desire.” In between the good and bad were the routine aggravations of a large deliberative body: the slow pace of work as it was farmed out to committees, and the squabbles over preliminary matters, such as payment for extra stenographers and messengers, before the “mill will begin to grind, turning out its grist of good and bad laws.”

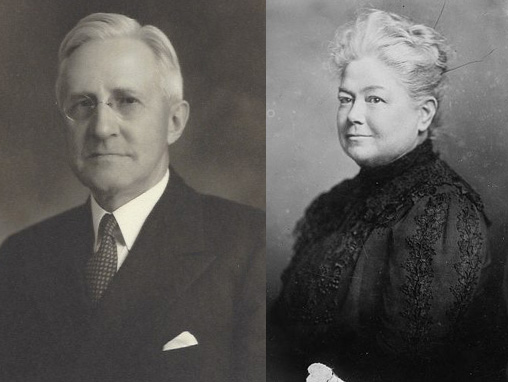

On January 13, Coke’s own capacity to do good was tested when he voted to table a resolution inviting leading woman suffragists Laura Clay and Madeline McDowell Breckinridge to address the House. An opponent of woman suffrage, Coke nevertheless thought the brushoff “very discourteous” to these nationally known Kentucky women; he made a motion to reconsider, and the resolution was adopted.

When the women appeared before a joint session on January 15, however, Coke’s gallantry seemed to fade. Laura Clay, he sniped, “is a very large woman with a very flabby pugnacious face, in fact she would make a child hide under the bed if it did not know she would not eat it. Mrs. Breckinridge is a very frail consumptive looking woman of 30 or 35 years who is a granddaughter of Henry Clay.” They “made fine speeches,” he admitted, “but I do not think they changed anyone’s mind.” Coke’s estimate that the legislature stood “about three to one” against suffrage might have been accurate, but Clay and Breckinridge, as they say, persisted. Six years later, Kentucky became one of only four southern states to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteeing women the vote.

J. Guthrie Coke’s letters from Frankfort are part of the Coke Family Collection in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here for a finding aid and full-text download. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.