A descendant’s recent donation to WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections of the letters and papers of the Weirs, a prominent 19th-century Muhlenberg County, Kentucky family, has provided rich insights into the Civil War history of that county (here and here, for example). Another wonderful item in this collection is the journal of patriarch James Weir (1777-1845), who emigrated to Muhlenberg County from South Carolina. En route in 1798, Weir sojourned in Knoxville, Tennessee and taught school for several months.

Shortly after posting our collection finding aid on TopSCHOLAR, we received an inquiry about the Weir journal from Knoxville librarian Steve Cotham. He had seen excerpts in typescript, but was interested in the original because it was long thought to contain “the first reference to African American banjo music” in that part of Tennessee. Indeed, James Weir’s journal has been cited several times as the source for this interesting tidbit of musical history.

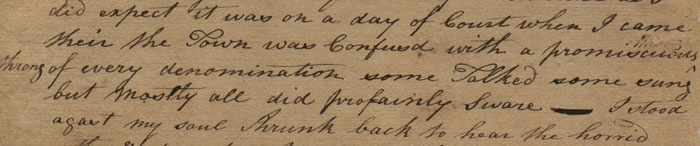

Having only recently processed the collection, however, we knew something was amiss. Arriving in Knoxville on County Court day, the pious Weir had written that he found a rollicking town, “Confus[e]d with a promiscuous throng of every denomination some Talked some sung but mostly all did profainly sware – I stood ag[h]ast,” he declared, “my soul shrunk back to hear the horrid oaths and dreadful Indignities offered to the supream Governer of the universe.” Weir was further mortified to witness “dancing singing & playing of Cards,” and on a Sunday, no less.

It’s a vivid portrait of a frontier community, but nowhere in Weir’s description is there a reference to either African Americans or banjos. So how did this source become part of the body of scholarship on African American banjo music?

Here’s what probably happened:

In 1913, Greenville, Kentucky’s Otto Rothert gained access to the journal when he wrote about the Weir family in his book A History of Muhlenberg County. He quoted accurately from its pages, with only minor edits for spelling and punctuation. But then along came Robert M. Coates with his 1930 book The Outlaw Years: The History of the Land Pirates of the Natchez Trace. Writing of the notorious Harpe brothers and their criminal exploits in Knoxville, Coates used James Weir as a source for his portrait of the city. In what looked deceptively like a paraphrase of a passage from the journal, Coates declared that Weir saw “men jostling, singing, swearing; women yelling from the doorways; half-naked n—–s playing on their ‘banjies’ while the crowd whooped and danced around them.” Mixing quotation and invention, Coates continued: “The town was confused with a promiscuous throng of every denomination”—blanket-clad Indians, leather-shirted woodsmen, gamblers, hard-eyed and vigilant — “My soul shrank back.”

This embellished version of Weir’s journal, including the sudden appearance of “banjies,” took on a life of its own. The reference was picked up in 1939 by the Federal Writers’ Project in Tennessee: A Guide to the State (where the racial epithet was changed to “Negroes”). It appeared again in Cecelia Conway’s African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia (1995) and in George R. Gibson’s 2001 article “Gourd Banjos: From Africa to the Appalachians.” With the original Weir journal in private hands until only recently, it was perhaps impossible for scholars to locate and check the original; in any event, the colorful prose of Coates, who spent most of his career as a novelist and art critic, must have been too good to overlook. The story of the banjies-that-never-were is a lesson for all historical researchers: whenever possible, go straight to the source. And with James Weir’s journal in our collection, now they can.

Click here for a finding aid to the Weir Family Collection. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.