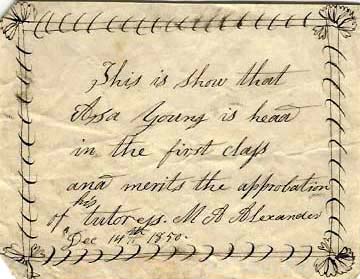

“This is to show that Asa Young is head in the first class and merits the approbation of his tutoress.” Dated December 14, 1850, this handwritten and decorated slip of paper would have been, like all good news, proudly delivered to the young schoolboy’s parents in Barren County, Kentucky.

Collections in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections show generations of Kentucky students receiving an “A,” “B” or “C” for their three Rs, but their report cards also judged them on habits and values deemed crucial to their development as adults.

Bowling Green student William J. Potter‘s third-grade report cards for 1908-09 recorded his days present, absent and tardy, and gave numerical grades for his classroom work, but included a “Verbal Merit Report” evaluating less tangible attributes like “Progress,” “Effort” and “Deportment”–which, parents were advised, was “a better index to what your child is doing in school than the scholarship report.”

Charles Ranney‘s second-grade report card for 1930-31 at Hartford Graded School was full of “As” for scholarship, but also required his teacher to evaluate “Interest” (from “Lacks Interest” to “Very Interested”) and “Conduct” (from “Rude,” to “Annoys Others” to “Inclined to Mischief” to “Very Good”).

Myrtle Chaney‘s seventh-grade report card from Logan County in 1922 was even more exacting in its standards. A bad attitude toward school work might get a check mark beside “Indolent,” “Wastes Time,” “Copies; Gets Too Much Help,” or “Gives Up Too Easily.” Less than good behavior could peg one as “Restless; Inattentive,” “Whispers Too Much,” or “Discourteous at Times.”

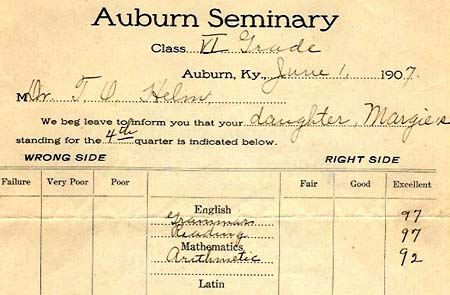

Margie Helm‘s 1908 report card from Auburn Seminary was set up like a ledger, with her subjects listed down the middle between the “Right Side” (a choice of “Fair,” “Good” or “Excellent”) and the “Wrong Side” (a choice of “Poor,” “Very Poor” and “Failure”). As was common, the back of the report card preached about the value of a parent’s contribution in securing regular attendance and study.

Occasionally, however, the year-end evaluation reminded everyone of their fallibility. Sarah Richardson‘s 1958 report card from College High cast her in an approving light, but the document somewhat undermined its credibility with the heading “COLLEGE HIGH RPEORT CARD.”

Click on the links to access finding aids for these collections. For others relating to schools, students and report cards, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.