Like many young couples in the 19th century, they courted through their letters. After they met early in 1880, Nellie Gates, 24, of Calhoun, Kentucky and Robert Coleman “Coley” Duncan, 26, began a correspondence. Their face-to-face time was limited, as Coley’s travels selling for a wholesale grocer regularly took him to communities along the Green and Barren rivers between Calhoun and Bowling Green.

Coley’s letters covered the usual topics: gossip about their mutual friends, his reading, his travel accommodations, and plans for their next meeting. He also expressed some envy of potential rivals for Nellie’s affection, and urged her to ignore warnings from old flames about his suitability as a correspondent. Nellie’s replies must have been encouraging, for by late 1880 he had declared his love and by early 1881 they were engaged.

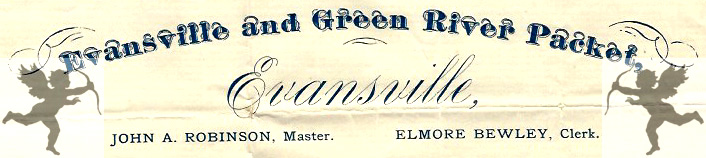

The couple tried to keep their plans to themselves, but when Coley boarded the Evansville and Green River packet steamboat to make his sales rounds, he found himself warding off the curiosity of one particular onlooker: the captain, Elmore Bewley, who knew not only Coley but many of the region’s young people through their leisure travel on his craft. “Capt B. told me as I came up the river,” he wrote Nellie, “that he had seen you that day and went on with the usual compliments he pays you whenever he speaks of you to me.” A few months later, Coley expressed his annoyance to Nellie after Bewley asked him if their engagement “was not satisfactorily settled. . . . He looked at me like he knew all about it.” When Coley insisted that Nellie had given him the brush-off, Bewley “didn’t believe it and was going to ask you about it.”

But pointed questioning wasn’t his only device. Bewley’s sleuthing skills were enhanced by the fact that his boat also carried the area mail. Coley was reluctant to post too many letters on board “because those steamboat men are such accomplished talkers. They all see the letters – know just who corresponds and make that the topic for their remarks to the public.” Visiting the boat’s mail room, Coley himself had spotted a letter addressed to one of his friends “in a lady’s handwriting.” As far as his own correspondence, he declared that if he were to mail a letter to Nellie “two Saturdays in succession,” he would be handing the boatmen “a rich morsel to roll under their tongues.”

Ultimately, the stress of controlling public perceptions of their relationship, combined with a host of other insecurities and misunderstandings, were too much for Coley, and he broke it off with Nellie a little more than a year later. How Captain Bewley took the news is unknown, but it’s possible he figured out – even before the principals did – that the affair had “sunk.”

Robert Coleman Duncan’s letters to Nellie Gates are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more courtship letters, search TopScholar and KenCat.