In summer 1913, life was becoming intolerable for Nannie England. The 35-year-old Bardstown native had lost her husband Alfred to tuberculosis two years earlier, her 11-year-old son Edward had just been accidentally killed in a dynamite explosion, and the mortgage on her home was in default. But Nannie, described as “refined, cultivated and capable,” was determined to support herself and her three surviving children by becoming the next postmaster of Lebanon, Kentucky.

The incumbent postmaster was due to leave office in April 1914, and the vacancy would be filled by President Woodrow Wilson upon the recommendation of Ben Johnson, the member of Congress for Nannie’s district. The good news for Nannie: Ben Johnson happened to be her cousin. The bad news: Johnson had already given his early and public endorsement of local farmer John B. Wathen for the position.

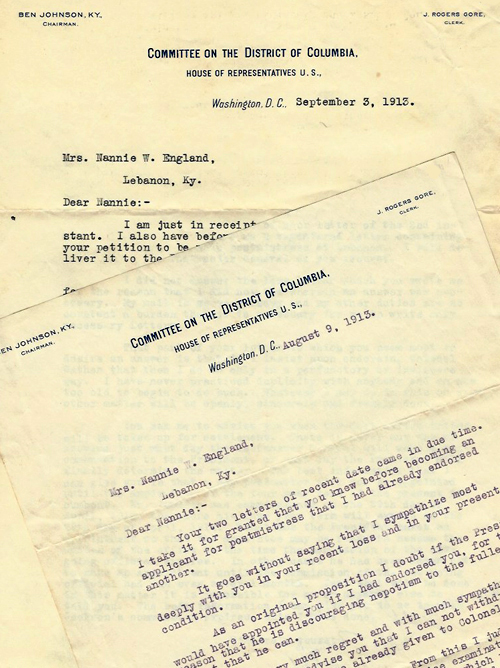

Congressman Johnson explained his quandary in a letter to Nannie. Having extended his support for Wathen, he was loath to pull the endorsement or even walk it back to some milder expression of goodwill. Furthermore, President Wilson was unlikely to approve her appointment since he was “discouraging nepotism to the fullest extent that he can.” Johnson encouraged Nannie to take the civil service exam, then pursue some other position in the postal or internal revenue service.

Completely undeterred, Nannie and a large circle of loyalists began a ferocious campaign to gain Johnson’s surrender. Her letters implored him to “lift me and my babies out of the mire, where we have been struggling ever since the death of my husband.” Referring to her rival, she declared “I am as competent as Mr. Wathen” to hold the position. She presented a petition signed by most of the patrons of the Lebanon post office, and warned Johnson of the political fallout that would arise from his neglect of the popular will. She gathered letters of endorsement from Lebanon’s business community and even from members of Wathen’s family, who claimed that his misplaced ambition, unpopularity with the locals, and mistreatment of his children disqualified him from consideration. Nannie suggested that Johnson find some other emolument for Wathen, knowing “so many good positions . . . that could be acceptably filled by a man, and the post office duties so peculiarly suitable to a lady.”

As the time for filling the position drew near, Nannie and her supporters intensified their efforts. “Her heart and soul are in this fight,” wrote one of her backers. Nannie appealed to Johnson’s wife (“cousin Annie”) and to her Senator, Ollie James, to bring some pressure on the Congressman. She asked to meet personally with the Postmaster General in Washington, D.C. before the appointment was made. The beleaguered Johnson, now hopelessly boxed in by his premature endorsement, was even presented with another scheme by one of Nannie’s allies: that he make her Postmaster and mollify Wathen by appointing Wathen’s daughter Edith, a capable young woman who had recently passed the civil service exam, as her “first assistant.” (One wonders how much Nannie knew of this proposal since it would have involved dividing the salary 50-50, an unlikely compromise for two male candidates.)

Alas, the story has an all-too-familiar ending. In spite of Nannie’s spirited campaign, John Wathen became Lebanon’s postmaster and remained there for more than a decade.

Correspondence regarding Nannie England’s application for Postmaster is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.