In an April, 1848 letter to his nephew Robert in Marshall, Illinois, Woodford Dulaney discussed the family fortunes, both economic and personal. Writing from Cloud Spring Farm in Warren County, Kentucky, Dulaney had advice for Robert, who was overseeing some business interests in Illinois. He gave him instructions regarding the renewal of a store lease to one Greenough (“do so in black and white and bind him up close and have an eye to his neglect . . . for certainly he does not take any care of the property”). He also sympathized with Robert’s travails over the settlement of an estate (“I am in hopes if you have to resort to the law, you may have justice”). Dulaney reported that family health was mixed: “Your Aunt Nelly can’t stand it much longer has a very bad cold & cough,” but Robert’s 3-year-old cousin and namesake, Robert Fenton Dulaney, was “a bouncing boy & is cock of the walk.” Dulaney then cast an analytical eye on the local economy: “The merchants in Bowling Green are bringing on very heavy stocks of goods & selling them very low.” This was too tempting for the farmers, he worried, “for when goods are low they buy extravagantly.”

In an April, 1848 letter to his nephew Robert in Marshall, Illinois, Woodford Dulaney discussed the family fortunes, both economic and personal. Writing from Cloud Spring Farm in Warren County, Kentucky, Dulaney had advice for Robert, who was overseeing some business interests in Illinois. He gave him instructions regarding the renewal of a store lease to one Greenough (“do so in black and white and bind him up close and have an eye to his neglect . . . for certainly he does not take any care of the property”). He also sympathized with Robert’s travails over the settlement of an estate (“I am in hopes if you have to resort to the law, you may have justice”). Dulaney reported that family health was mixed: “Your Aunt Nelly can’t stand it much longer has a very bad cold & cough,” but Robert’s 3-year-old cousin and namesake, Robert Fenton Dulaney, was “a bouncing boy & is cock of the walk.” Dulaney then cast an analytical eye on the local economy: “The merchants in Bowling Green are bringing on very heavy stocks of goods & selling them very low.” This was too tempting for the farmers, he worried, “for when goods are low they buy extravagantly.”

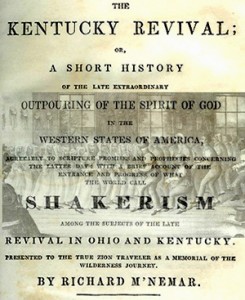

But Dulaney also had religious news, in particular of some recent activity in the local Shaker community. The 1840s was a decade of national revival, and in Shakerism it manifested itself in the dedication of a plot of ground where members assembled in the spring and fall, according to historian Julia Neal, to “commune with the voice and receive the great outpouring of the spiritual.” From what Dulaney had heard, however, this gathering promised to be unusual both in its size and public nature: a veritable 19th-century Woodstock, with the Shakers’ unique demonstration of devotion, their rhythmic marching and ecstatic dancing, much in evidence. “[T]he Shakers have commenced worship again they jump higher & quicker than ever,” Dulaney told Robert, “and on Monday the 1st day [of] May they are going to worship out in a grove”–a 10-acre tract, no less, which they had cleared in order to give themselves “a far sweep.” Likening the worshipers to frolicking creatures of the field, Dulaney declared “I intend to go and see them cut capers.”

Woodford Dulaney’s letter is only one of many sources on the Kentucky Shakers in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives holdings of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here to access a finding aid. For more collections about the Shakers and other religious faiths, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.