Directors and officers. Company history. Operational schedules. Location(s). Lists of products and services. Achievements and awards. Images of massive factories, office towers or other icons of prosperity. Today, we would expect to see this type of publicity and promotion on a web page or a social media site. But more traditionally, it was crammed onto the principal means of pre-internet communication for an individual or business: a sheet of letterhead.

WKU’s Special Collections Library has many examples of such items. Some might regard them as ephemera, but they are often historically rich documents: artistic, colorful, and chock full of information about what people did and how they did it before the electronic age. Here are some examples:

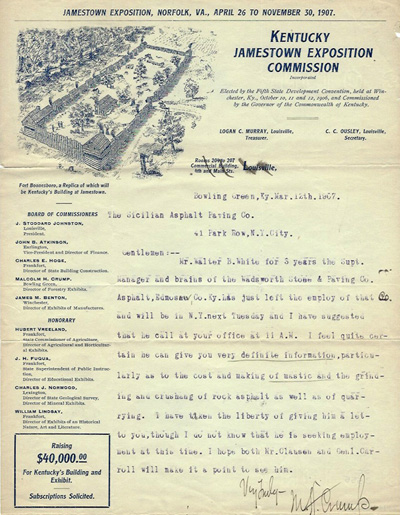

Over the signature of Commissioner Malcolm Crump of Bowling Green, the letterhead of the Kentucky Jamestown Exposition Commission, created in 1906 for the state’s participation in a fair celebrating the 300th anniversary of Jamestown, Virginia, described the project’s origins and administration. Text in the lower left corner solicited funds for Kentucky’s contribution, impressively rendered in the upper left corner: a replica of its second white settlement, Fort Boonesboro.

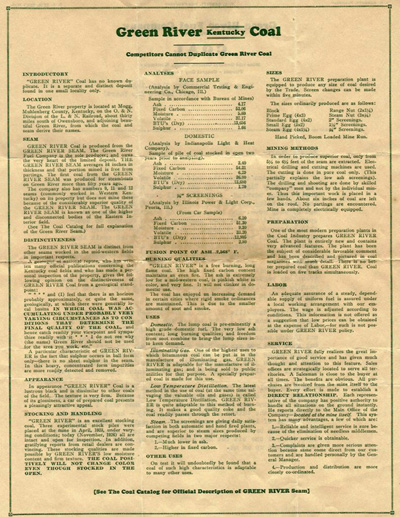

In 1926 a young man known to us only as “Boots” typed a chatty letter from “the wilds of Kentucky” to a lady friend in Nashville, but the reverse of his letterhead (or presumably that of his employer) bore a Wikipedia-style entry about the Green River Fuel Company of Muhlenberg County and its product, “Green River Coal”: where it was, its appearance and uses, how it was mined, and why “Competitors Cannot Duplicate” its quality.

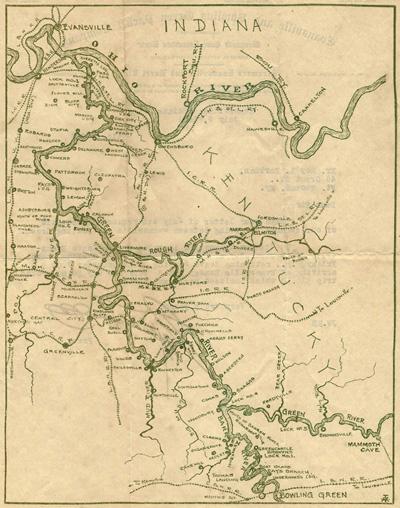

Similarly, in 1931 the reverse of riverman Jeff Williams’ letter gave patrons of the Evansville and Bowling Green Packet Company a Google Maps-style directory of its steamboats’ many ports of call along the Green and Barren rivers.

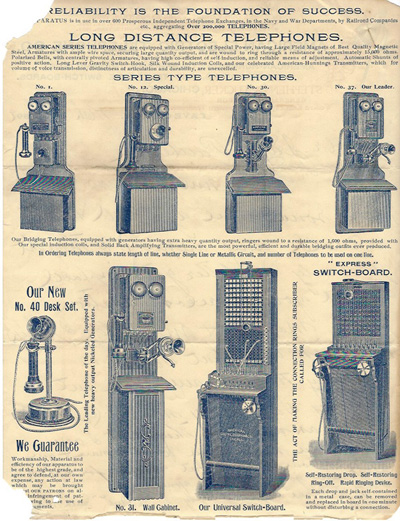

In a page that could have been taken from a Sears catalog, the reverse of a young man’s 1899 letter to his uncle showed the product lines—from desk sets to wall units to switchboards—of the American Electric Telephone Company, with offices in Cave City, Kentucky.

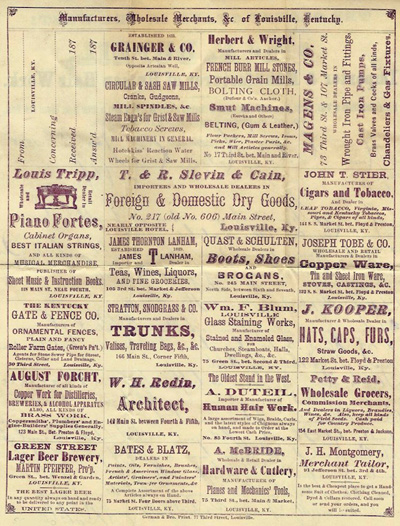

The 1870s equivalent of pop-up ads appeared on the reverse of the letterhead of Alphonse Duteil, a Louisville “Importer & Manufacturer of Human Hair Work.” More than 20 data-heavy ads showed Duteil in good company among the city’s manufacturers, dealers and wholesalers.

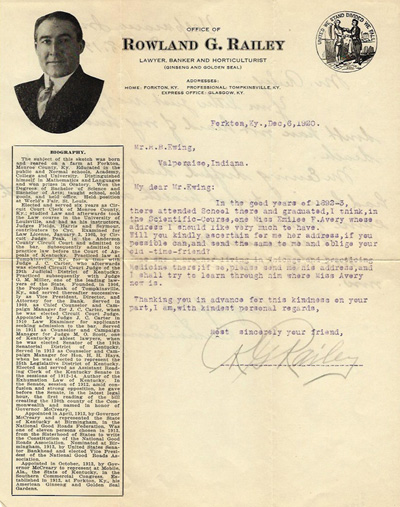

In lieu of a Facebook page, in 1920 Monroe County “Lawyer, Banker and Horticulturalist” Rowland G. Railey unfurled his biography down the front left-hand side of his letterhead.

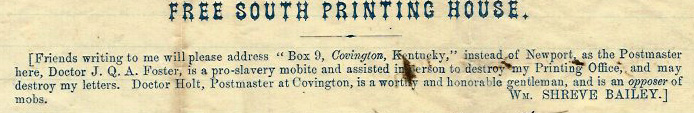

And how’s this for the Civil War-era equivalent of a pinned tweet? William Shreve Bailey of Newport, Kentucky, editor of the abolitionist newspaper The Free South, inscribed his letterhead with instructions to correspondents to address him at a post office box in Covington. The reason? Besides enduring threats and a mob’s destruction of his press, Bailey suspected that the Newport postmaster, “a pro-slavery mobite,” might simply pitch his letters in the trash.

Click on the links for finding aids and full-size scans of these letters. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.