Sir, the letter began:

The receipt of your letter occasioned me some surprise, especially as it treated on a subject to which I had not yet devoted my thoughts; neither did I imagine, from the general tenor of your conduct towards me, that you entertained the sentiment you have thus avowed.

Uh oh. This foretold heartbreak for the recipient, who had obviously made the decision, sometime early in 1857, to declare his love for 22-year old Marie McCutchen of Logan County, Kentucky. Her brief but masterfully composed rejection, however, let him down easy in the gentlest of terms:

Trusting you will suffer your natural and good sense to conquer a passion which can never need a due return from me. I return to you my very grateful thanks for the honor you have done me, and at the same time assuring you that you will ever possess my faithful friendship.

Among the many courtship letters in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections are those chronicling relationships gone wrong, or, like Marie’s, nipped in the bud (perhaps wisely, in her case: her suitor was twenty years older and had already been married twice). It’s not known if he replied to Marie, but some spurned lovers find that a letter back is the best forum in which to plead their case. In 1918, a young WKU coed received a reply to what her (now) ex termed her “confidence jarring” break-up letter. “We shall always remain friends,” he declared, giving himself good grades for his manly conduct. While he wished her luck in her “Cupidistic affairs,” he laid on a little bit of a guilt trip, hoping that she wouldn’t regret her decision and vowing to fight hard for the hand of the next “Fair Lady” who came along. Though gainfully employed, he also warned that he would likely be off to serve in World War I soon and . . . please, could she at least send a photograph?

Similar face-saving appeared in the letter of a young Woodburn man to his sweetheart only a year later. “I have got some good news for you I am going to leave Ky in September,” he announced. Another suitor had intruded upon their two-year relationship, leading him to realize “that you don’t care anything about me.” He admitted, nevertheless, that “I never expect to meet another girl that I could love like I love you.” In 1882, Robert C. “Coley” Duncan had confronted the same dilemma when he wrote to Nellie Gates of Calhoun, Kentucky. “You love someone more than you do me I feel sure of it and it would certainly be best for both of us to cancel our engagement.” Robert, in fact, married someone else only a year later, while Nellie’s rather cryptic reaction was to save his letter – in eight torn-up pieces.

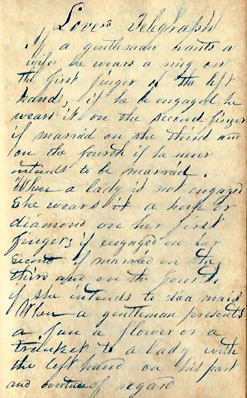

If some courtships start as well as end with a letter, perhaps no finer specimen can be found in our collections than one lengthy, unsigned, undated appeal, perhaps drafted and then carefully rewritten – or hidden away by an author who lost his nerve. Dear Miss, it began. For fear that a conversation with her would arouse gossip, he had resolved to take this approach:

Feeling my situation to be a forlorn lonesome & unhappy one I have seriously considered the propriety of writing myself to some tender hearted female calculated to soothe my sorrows and to enjoy with me the pleasures this uncertain world is able to afford. . . .

And in considering where I could find one in whom I could have that confidence in their good sense and propriety of conduct necessary to a happy Union my mind seems involuntarily to center on you. . . . And I must acknowledge to you that I have existing within my breast feelings of a very tender and inexpressible kind for you that I do not feel for any other person. . . .

And now I would candidly ask you whether you could consent to enter into a matrimonial connexion and whether your affections are disengaged. . . . If you would condescend to answer me by letter it would meet my warmest approbation. . . . let your answer be plain & candid if you could subscribe the following it is all that is necessary: “I will share your sorrows and you shall share my Joys.”

Let’s hope he got his answer.

Click on the links to access finding aids for these collections. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.