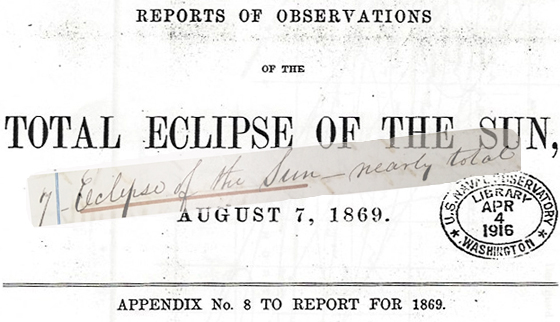

As we all know, a total eclipse of the sun will pass over southcentral Kentucky in the early afternoon of August 21, 2017. The last time such an event occurred in this area was August 7, 1869, and the tiny Warren County community of Oakland was expected to provide a prime viewing spot.

Four days before the eclipse, Professor Samuel Pierpont Langley, an eminent astronomer and later Secretary of the Smithsonian, arrived by train with a colleague to set up his observation post at Oakland. Finding only a few houses in the vicinity of the station, he moved two small sheds to a field near the tracks and procured a telegraph connection. He set up his telescope and other instruments, conducted some practice sessions, and prepared for the big event.

But Langley’s splendid scholarly isolation was not to last. “On the afternoon of the 7th,” he reported, his station was overwhelmed by “all the inhabitants of the adjoining country, white and black, who crowded around the sheds, interrupted the view, and proved a great annoyance.” As if that wasn’t enough, just as the eclipse neared its total phase, a special train pulled in carrying onlookers from Bowling Green and–of course!–a brass band.

Langley soldiered on with his work. He calculated the duration of totality, when the moon completely obscured the sun, as lasting only a second or two, far less than the 30 seconds he expected. Nevertheless, he was able to see the sun’s corona “visible through the darkening glass as a halo close to the sun, whence radiated a number of brushes of pale light.” He felt particularly fortunate to get a 15-second view of “Baily’s Beads,” the effect produced when the disappearing sun backlighted the moon’s uneven surface–“like sparks,” he reported, “upon the edge of a piece of rough paper.”

In Bowling Green, druggist John E. Younglove noted the eclipse in his meteorological journal. Though brief, the totality was sufficient to “observe the Corona with its variegated Colors.” The eclipse also merited an entry in the daily journal of the Shaker colony at South Union–“nearly total here.” Writing a history of Oakland in 1941, Jennie Bryant Cole conceded that the astronomers’ better position “should have been about one mile farther up the railroad”; nevertheless, when the “country people came in” and the crowd and brass band arrived, and when the stars suddenly came out in the afternoon and the chickens went home to roost, it was a “memorable day for Oakland.”

Click on the links to access finding aids for collections in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections relating to the eclipse of 1869. For more firsthand accounts of eclipses, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.