On February 6, 1974, a resolution of the House of Representatives gave the Judiciary Committee authority to investigate the possible impeachment of President Richard Nixon over the Watergate scandal. Watching the proceedings closely was Kentucky’s Fifth District representative, Republican Tim Lee Carter. Serving the fifth of his eight terms, the physician from Monroe County had brought his own causes to Congress, including a plan for national health insurance and, in 1967, a call to end to the Vietnam War. With respect to impeachment, however, Carter was a strong defender of Nixon and, as he would later point out, was the first member of Congress to give testimony on the President’s behalf.

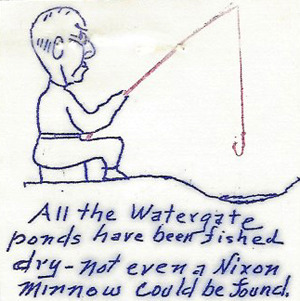

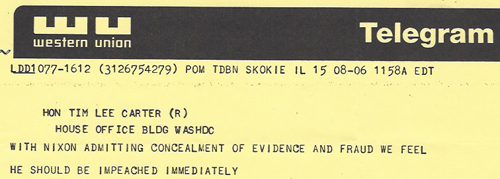

Like other legislators, Carter heard plenty from voters in his district and around the country on the question of impeachment. From October 1973 to November 1974, he received hundreds of letters, cards, telegrams, petitions and preprinted cards from both supporters and opponents of the measure. Some were brief – “Censure Yes Impeachment No” read a terse telegram from a couple in Coral Gables, Florida — while another telegram from California declared: “Immediate impeachment and trial of President essential to country nothing less will serve act promptly.”

Many communications, not surprisingly, were lengthy and passionate. “President Nixon is the victim of a relentless witch hunt,” wrote a Missouri couple. “We urge that you stand firm and cast your vote against impeachment.” From Richmond, Kentucky, an EKU faculty member wrote, “I think this nation cannot stand to allow people in high offices to get away with unconstitutional acts. . . . Nixon will accomplish not a generation of Peace but a generation of under-the-table crooked deals!” Some saw mere partisanship—“Why are the democrats stirring up such a fuss over campaign donations when they are spending and wasting so much money trying to drag up some evidence to impeach Pres. Nixon?” asked a couple from Summer Shade, Kentucky. “The envy, harassment, venom of the Media and Leftists would destroy the U.S. to get Nixon,” came from Mount Vernon, Kentucky.

Others took the longer view. “We have to have faith in the truthfulness of our leaders, and he [Nixon] has caused us to be sadly skeptical of every word he says . . . since he and his aides still persist in covering up and fighting the investigations, he must be impeached by Congress,” a writer argued from Barbourville, Kentucky. “There is so much evidence of wrongdoing committed to enhance the President’s power, his prestige, or his individual niche in history, that I no longer trust his leadership. If allowed to remain in office, Mr. Nixon will probably continue the pattern he has set,” concluded a voter from Monticello, Kentucky, conveying “a sincere expression of a tragic concern” and “not another anti-Nixon vendetta.” Congressman Carter wanted to maintain the focus on Nixon’s positive achievements, particularly in the area of foreign policy, and some of his constituents made clear that distressing domestic issues such as energy and food prices, taxes, abortion, and perceived media bias were coloring their opinions of the impeachment crisis.

Even after the Judiciary Committee approved articles of impeachment and Nixon resigned on August 8, 1974 rather than face trial in the Senate, the letters to Congressman Carter continued. Words like “traumatic” and “tragedy” appeared, as did expressions of both support and opposition toward granting the President a pardon or immunity from prosecution. A week after the resignation, Carter regretted that Nixon’s administration had been “involuntarily terminated” but looked with gratitude to the Constitution and its provisions for a smooth transfer of power. “Recent events,” he wrote, “have clearly demonstrated the strength of our government, our people, and the principles that have guided us through our great history.”

Letters to Congressman Tim Lee Carter regarding the impeachment inquiry into President Richard Nixon are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more political collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.