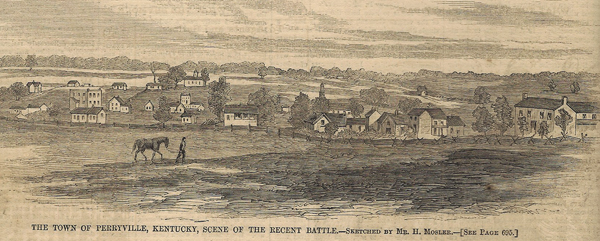

Everyone seems to agree that the most haunted town in Kentucky is Perryville, especially the Civil War field where, on October 8, 1862, some 7,600 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded in a battle that ranked as the second bloodiest in the Western theater up to that date.

While some 36,000 troops actually fought each other, twice that number were in the area at the time. One of the soldiers who narrowly missed the fighting was John H. Gray of the 101st Indiana Infantry, but his impressions of the battle’s gruesome aftermath can indeed make us think about the paranormal byproducts of such carnage.

Gray had arrived in Perryville exhausted and hungry, having subsisted for several days on virtually no rations. He and his comrades had lived off handfuls of wet cornmeal fried in a skillet (“corn kake”) some “fat meat” of undetermined origin, and a “coffee pot full of honey,” said to have been bought but more likely stolen. Gray’s constitution was not the only one to collapse on such a diet. He found the road from Springfield to Perryville “well perfumed,” as many of the men “had the ‘quick step.’” Gray himself, weak with diarrhea and vomiting, rode the last few miles in an ambulance.

As his regiment straggled into Perryville and collapsed to recuperate, Gray described the scene in two letters to his parents and siblings. “The horrors of War are apparent everywhere,” he wrote. He was particularly shaken at the sight of a “dead rebel this morning lying on the ground,” his face blackened with decay. “O how horrible,” Gray exclaimed, “a man left upon the field to rot unknown & uncared for.” Gray was “in a comfortable house attended by a good Doctor,” but all around him were other houses filled with wounded and dying men. He visited two hospitals, one treating Confederates and the other Federals, and was appalled by the “awful agony the intense suffering and the inexpressible pain of the occupants.” Those able to rise from their beds were “lame & wounded hobbling about as though this was a world of cripples.”

Accompanying the men’s physical pain was mental anguish. Gray spoke with Confederates who cried that they were tired of war, and were ready to vote to “lay down their arms and be as they were.” Some of these men, no doubt, died with Gray’s sarcastic observation—lovely war—on their lips. They may or may not haunt Perryville today, but they surely haunted the memories of the men, like Gray, who survived.

John Gray’s two letters written in the aftermath of the Battle of Perryville are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here and here for finding aids. For more Civil War collections, click here or search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.