Things were simpler back then . . . not. As we race to conclude the current (though extended) tax filing season, here’s how a member of the Carley family of Georgetown, Kentucky once puzzled through the process of “rendering unto Caesar.”

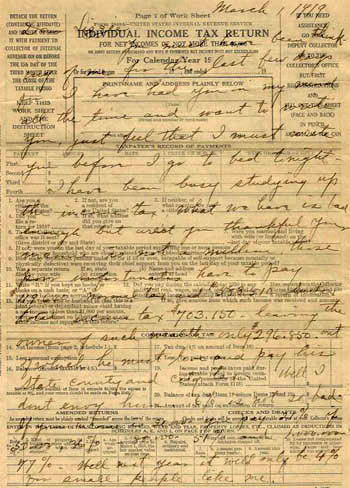

A native of Ontario, Canada, George Carley took his family to Kentucky via Pennsylvania in the 1870s. One daughter, Lizzie, remained at home and another, Georgia, married and moved to Arkansas. As World War I unfolded, the family saw income taxes rise dramatically to accommodate the costs of American involvement in the conflict (a war for which Georgia’s cousin Maggie Fortune, still living in Canada, had some choice words). In any event, on March 1, 1919, Georgia wrote sister Lizzie of her attempts to understand the Revenue Act of 1918. The revised law imposed a “normal” tax of 6% on the lowest bracket and 12% on higher incomes, but the real pain came with an additional, graduated surtax: on 1918 incomes over $1 million, it brought the government’s bite to a whopping 77%. The Act promised some relief for 1919 incomes, but not much: the normal tax would drop by a few percentage points, while the surtax remained intact.

Georgia carefully studied the helpful information provided by her bank, not only to understand her own obligations but to assess what emotions—jealousy, sympathy, or schadenfreude—she should reserve for better-off Americans. “What we have is bad enough,” she wrote Lizzie, “but aren’t you thankful your income is not a million.” She had checked the charts and discovered that “those poor unfortunates” would have a normal tax bill of $119,640 and a surtax of $583,510, “leaving the owner of such wealth only $296,850 out of which he must live and pay his state county and city tax. Well I don’t envy him.”

Given that $296,850 had the purchasing power that $5.2 million does today, Georgia was probably being sarcastic. However, at a normal rate of 6% and a surtax rate of zero, the grab on her own income (which we can deduce was less than $4000) was “not so bad”—and the next year, she reported, “it will only be 4% for small people like me.” She gave a gentle reminder to her sister to “get your report in before March 15”—a date that would remain the deadline for tax filers until changed in 1954 to April.

The Carley family’s letters are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more collections, search TopScholar and KenCat.