Streaking across the political firmament in the 1850s, the American Party rose in response to a wave of immigrants, many of them Catholics, to the United States. The party saw the newcomers as a threat to American values and economic security, and feared that their allegiance to the Pope would compromise their loyalty to the country.

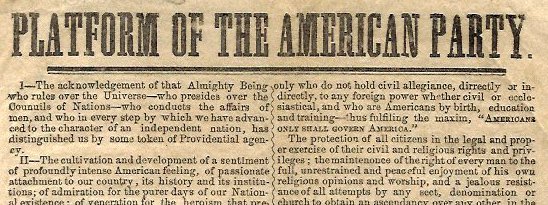

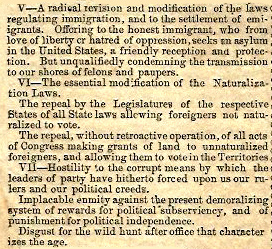

Collections in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections tell us of the interest the American Party attracted throughout the country. It was originally more of a secret society, with a formal admission ceremony described by Robert Hale, and a command to members to say “I know nothing” when pressed for their beliefs. The “Know Nothing Party,” as it came to be called, stood for restricting immigration, limiting eligibility for political office to native-born Protestants, and imposing a lengthy residence requirement for U.S. citizenship.

Although the Know Nothings were most prominent in the Northeast, they drew comment from every region. Writing from California to his father in Dry Fork, Kentucky, George Young observed that “the Know Nothings are increasing very fast” and “I am inclined to believe that it will do this state much good.” A more skeptical letter-writer in Texas told the Goodnight family of Warren County, Kentucky that party supporters “talk a great deal about true Americans but I don’t believe there is a true Republican amongst them.”

In a speech delivered in Virginia, Georgia native Michael Cluskey, later a newspaper editor in Louisville, offered a lengthy and increasingly passionate criticism of the Know Nothings. He debunked the “bugbear of immigration,” which was “made to appear frightful by the unfounded statements of certain Know Nothing orators.” Contrary to the claim that “there were 1000 000 million of emigrants into this country during the last year,” he pointed to actual native-born-to-immigrant ratios of 38 to 1 in Virginia and 8 to 1 in the U.S. A recent decrease in immigration, in fact, was threatening to cause a labor shortage, especially for public works like roads and canals, to which “native born Americans generally don’t choose to expose themselves.” As for the party’s anti-Catholic platform, Cluskey observed that “nothing is so easily stirred up in the breast of man as the serpent of Religious prejudice,” a “cry of wolf” through which politicians could achieve darker objectives. “Small temporary shocks like these,” he argued, were more dangerous to the republic than “direct blows at its stability.”

The 1856 presidential election, in which their candidate finished last, spelled the end of the Know Nothings. In a letter written from Madisonville, Kentucky, Charles Cook understood why. “I still cherish the leading principles of the American party as the only efficient guarantee against the dangerous influences and corrupting tendencies of foreign emigration,” he admitted, “but these are questions of minor importance.” The issue now roiling the country, and the one to which “the earnest efforts of every patriotic Union loving man should be turned,” was slavery.

Click on the links to access finding aids for these collections. For more collections relating to immigrants and the Know Nothings, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.