Issued on May 17, 1954 (and cited above), the U.S. Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas ruled that segregated schools deprived that city’s African-American elementary school students “of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.” The court threw out the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) that had upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation for more than half a century. (The lone dissenter in Plessy was Justice John Marshall Harlan, a Boyle County native and former Attorney General of Kentucky. “We boast of the freedom enjoyed by our people above all other peoples,” he wrote. “But it is difficult to reconcile that boast with a state of the law which, practically, puts the brand of servitude and degradation upon a large class of our fellow-citizens, our equals before the law.”)

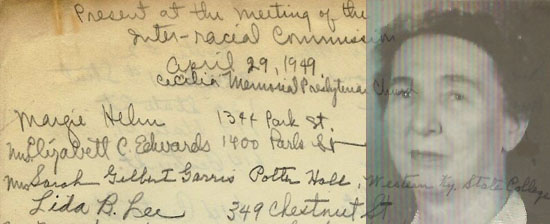

Long before the Brown decision, the inequalities fostered by segregation had become a concern for Margie Helm, WKU’s Director of Library Services. In 1947, during the rebuilding of Bowling Green’s public library after a fire, she and others seized the opportunity to establish a new branch for African Americans at 412 State Street. “As a librarian,” remembered her niece, Margie Helm “took quiet actions to help everyone have access to the books they wanted to read even before local public libraries were accessible to blacks.” In 1949, she joined Bowling Green’s Inter-Racial Commission, created to promote educational and vocational opportunities for African Americans in the city and surrounding counties.

On November 9, 1956, as the country struggled with the Supreme Court’s imperative to desegregate “with all deliberate speed,” Margie Helm, a thoughtful and lifelong Presbyterian, spoke to a local women’s club on “Attempts to Find the Christian Attitude Toward Integration of the Public School System.” She acknowledged “different attitudes toward integration” among her friends and colleagues, but cautioned her listeners to understand the difference between opinions and prejudices; the latter, as she quoted author Pearl Buck, should be “kept locked up in our hearts, like our tempers.” She also pointed out the illegitimacy of the “separate but equal” doctrine, which had not produced the educational or social results it claimed to guarantee. Calling attention to the relatively peaceful trends toward integration in cities like Evansville, Indiana, Louisville, and even at WKU, she urged fellow Southerners to read, think, empathize and, in the face of changing times, walk away from ancient prejudices. With the help of Christians, she believed, what was once a “great problem” would dissolve, little by little.

Margie Helm’s remarks and her other collected papers are part of the Manuscripts and Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. For more, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.