Bots and trolls aside, some of us may find our devices useful in making sense of the forthcoming election: to research candidates and polling places, request an absentee ballot, or get texts and updates from our favored office-seekers. But the “device”—in its more archaic meaning of an emblem, logo or design—took on a different significance in past American elections.

Late in the 19th century, some Kentuckians could still cast a vote by voice, but others going to the polls were liable to be handed a ballot printed not by an election authority but by a particular political party. One glance at the distinctive colors and markings of such “tickets” allowed voters to quickly register their preference, but unfortunately the process also made their votes public and, once deposited in the box, eligible for remuneration from the candidate with the deepest pockets and fewest scruples.

Kentucky’s mandate of a secret ballot in 1891 sought to diminish opportunities for fraud, but concern remained for the then-large number of voters who were unable to read. Accordingly, the state’s election law of 1892 prescribed the steps by which candidates, whether nominated by a party or put forward by petition, could appear on a ballot: in addition to “a brief name or title of the party or principle which said candidates represent,” they were to include “any simple figure or device by which they shall be designated on the ballots.” It could be “any appropriate symbol,” with a few exceptions: “the coat-of-arms or seal of the State or of the United States, the national flag, or any other emblem common to the people at large, shall not be used as such device.”

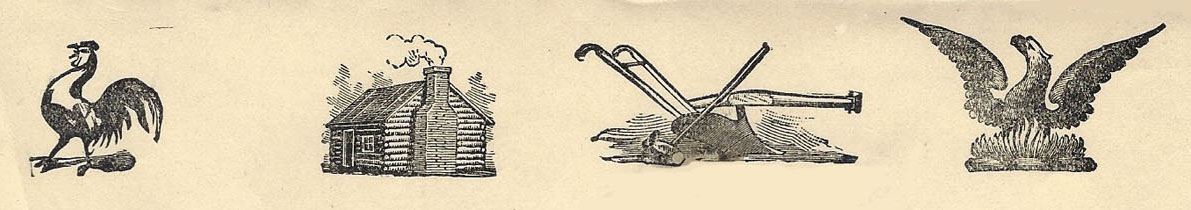

In October 1901, the Warren County, Kentucky clerk received instructions from Secretary of State Caleb Breckinridge Hill for balloting in the forthcoming state and local elections. As long as each of four parties had at least one candidate entitled to appear, their devices were to be shown as follows: “a game cock in the act of crowing” for the Democrats; a “Log Cabin” for the Republicans; “the Plow and Hammer” for the People’s Party; and “a Phoenix” for the Prohibition Party. The ballot should further display beneath each emblem the prescribed large circle in which voters could place an “X” indicating their endorsement of the straight party ticket. From there, it was up to the voters. Left to their own devices, on November 5 the county gave the Democratic ticket the lion’s share (or rooster’s, perhaps?) of 2,920 votes cast.

These ballot instructions to the Warren County Clerk are found in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For other collections on elections and balloting, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.

P. S. Need help this year? Check your ballot. . . the “devices” are still there!