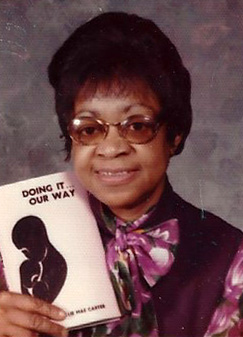

After graduating from State Street High School as its valedictorian in 1936, Bowling Green, Kentucky native Lillie Mae (Bland) Carter earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Tennessee State University, married, had four children, and pursued a career as a first grade and remedial reading teacher in the Toledo, Ohio public school system. A civic activist and champion of African American history and literature, Carter encouraged her students to express themselves through writing.

Carter herself was an author, editor and poet. Her books included Black Thoughts (1971), a volume of poetry, and Doing It Our Way (1975), an anthology of multi-generational poetry and prose. But like most writers, Carter encountered obstacles to getting her work published. This struggle helped her form a bond with one of the most prolific purveyors of the black experience to the world, the poet, author, playwright and icon of the “Harlem Renaissance,” Langston Hughes.

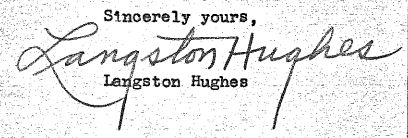

“The only way I know to achieve publication,” Hughes wrote Carter in 1947, “is to continually submit one’s work to magazines, and if it comes back (as it usually does) send it to others.” “Do not mind rejection slips,” he counseled. “I have hundreds of them.”

Over the next twenty years, Carter corresponded with Hughes, who critiqued her poems and offered advice on where to submit them for publication. He shared her frustration over editors who were reluctant to accept “race-problem” poetry or fiction, but recommended that she simply keep searching for others who weren’t so squeamish. Delighted with her poem, “Whispering Leaves,” he asked permission to send copies to the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American culture at Yale University, and to New York’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Hughes found poems she shared with him in 1963 to be “strong and dramatic and, I think, would make most effective program pieces to read aloud to audiences. I suggest you try them out the next time you have occasion to speak in public – or maybe you should create an occasion to do so.”

Carter dedicated Black Thoughts “In memory of my critic and friend, Langston Hughes.” It included the gentle “My Prayer,” which Hughes had praised (May I live from day to day / In an honest, sincere way; / That someone through me may see / What joys come from serving Thee), and a tribute to a former custodian at Toledo’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Elementary School (Keeper of the building, goodbye! / Rest well in new buildings on high). But also found in its pages were the mournful “Half-Still” (Half slave, half free / Half a citizen still / That’s me) and the bitter “America” (America is not red, white and blue / America is lily white – all the way through.)

Lillie Mae (Bland) Carter’s papers are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here for a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.