From his home near Cloverport in Breckinridge County, Kentucky, George L. Pate kept tabs on his large family: seven children from his 1835 marriage and, after his first wife’s death, five more from his 1852 marriage. Perhaps it was the strains of a blended household that had sent some of the children off to live elsewhere, including oldest son Samuel, who stormed out of the house early in 1861. Samuel wrote to his married sister Mary Jane mourning their late mother and pitying their other sisters still stuck at home “if I can call it home at all.”

But his trials with Samuel did not blunt father George’s affection for his other children. In March 1861, he wrote daughter Mary Jane of the death of her young stepbrother; two days later, he devoted the entire contents of another letter to an anguished account of the child’s illness, treatment, and forbearance in the face of suffering. The approach of the Civil War and the appearance of U.S. Army recruiting officers did nothing to alleviate George’s sorrows. “There is nothing talked of but war,” he wrote Mary Jane in July. “I am so tired of hearing it.”

“We are all true blue union men in this country,” Samuel Pate had assured his sister, but the Pates found their loyalties tested when Confederate guerrillas descended on Breckinridge County. Early in 1863, Mary Jane’s sister Sarah told of the rebels’ attempt to hang a member of their stepmother’s family after stealing his horse. Late in 1864, George wrote Mary Jane of the guerrillas’ charge into Hardinsburg, “cursing & swearing” and firing indiscriminately at the sheriff, at a local judge, and at any others who dared stick their “damed heads” out a door or window. When their captain was shot dead, the outlaws took to nearby roads, robbing George’s neighbors and taking every decent horse in sight. One such neighbor, William Basham, was carrying a cask of brandy; though relieved of his money, he was miraculously allowed to pass after giving the robbers a nail to make a hole and drink “what they wanted.”

A year earlier, William Basham’s daughter Sarah had married Joel Meadors, also robbed during the 1864 rampage. An incident just before the nuptials gave George Pate an opportunity to engage in some rare but wry humor. Meadors, he reported to Mary Jane, “has been shot” by none other than “his sweetheart.” It was, of course, an accident, and Sarah “never had any trial.” Observed George: “I have often heard of men being henpecked by women, but it seldom happens that a young lady that loves a young man well enough to marry him will shoot him.”

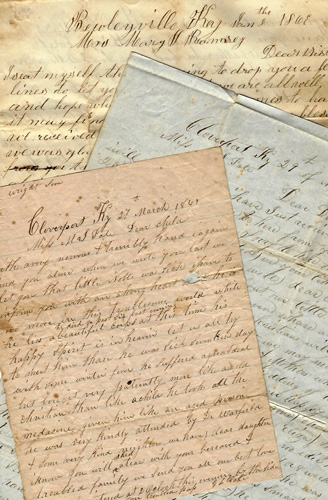

These and other letters of the Pate family have recently been donated to the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here for a finding aid, scans, and typescripts of selected letters. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.