Though he settled in Hancock County, Kentucky in 1845 at the age of 49, James Prentis retained his solicitude for his native Virginia – “the mother of States” – where he had grown up and studied law before taking up mercantile pursuits in Lewisport. There, he continued his family tradition of slaveholding, admitting that while he supported emancipation, he “dreaded any interference which would rashly precipitate such a result”; after all, he couldn’t see how he was “to get along comfortably and happily” without enslaved labor.

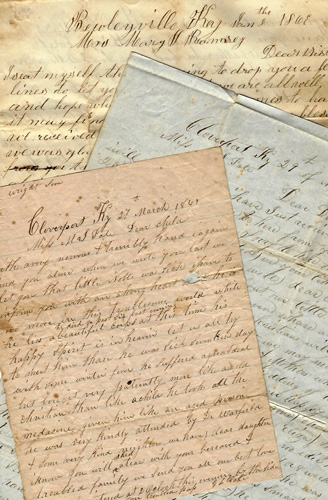

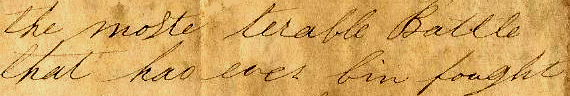

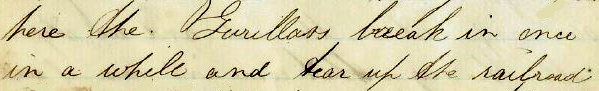

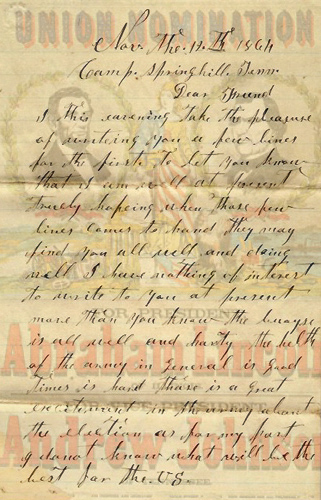

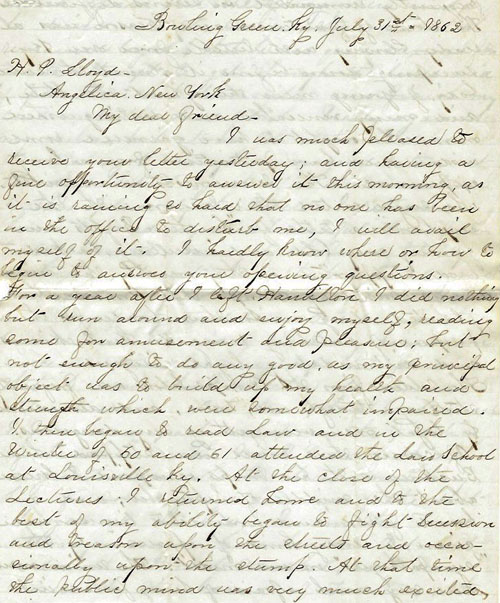

But as the secession movement intensified after the election of Abraham Lincoln, Prentis found himself looking across a political chasm at his fellow Virginians. From the onset of the Civil War through its aftermath, he drafted lengthy letters and essays, sometimes under the name “Senex” (“wise old man”) to friends and newspaper editors, deploring the foolishness of the South’s attempt to dissolve “our glorious Union” and condemning, in the starkest terms, those who incited, enabled, and led it.

Writing to an old Virginia friend in the spring of 1861, Prentis implored him to come to his senses; indeed, Prentis could only attribute secessionism to some sort of psychological breakdown – a “hallucination,” a “mental aberration,” a “sad and strange infatuation.” True, blame for the crisis could be divided between Southern secessionists and Northern abolitionists, but the latter were utterly feckless and easily suppressed, compared to the “immediate authors of our ruin – the Seceders South,” whose movement could be “likened to the frantic cowardice of the Tenant of an impregnable fortress who blows it up & himself with it, because a rollicking school boy explodes a pop gun against it.” So absurd did Prentis find the “doctrine of secession” that he could only attribute it to “the work of demag[og]ues & restless conspirators for selfish ends, the high & active attainments of some of whom have been freely used to poison the Southern mind & fire the Southern heart by an artful display of fancied wrongs.”

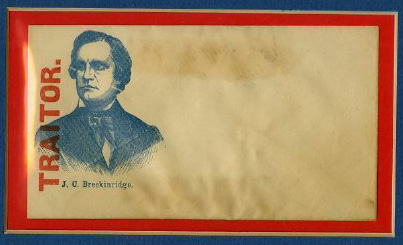

But whatever the roots of the doctrine, the applicable term for its adherents was traitor. Addressing his old college friend Edmund Ruffin, a former Virginia state senator and avid secessionist who was spotted on the battlements of Fort Moultrie in South Carolina, Prentis declared himself “astounded with the report that you are in collusion with the enemies of our Country & a particeps criminis in Treason – This I state merely as a fact, without intending the smallest imputations upon your motives.”

Even the Confederacy’s “crushing defeat” did not satisfy Prentis. What were you thinking? he seemed to say, complaining of the South’s stubborn refusal to accept moral guilt for its “reckless & insane effort” to destroy the “civil & religious liberty bequeathed to us by our revolutionary fathers.” Writing to another Virginia friend, he sternly mocked the South’s failure to take seriously the “terrible rights & necessities of war” and the expectation that “you would, of course, be immediately restored to all your rights forfeited by Rebellion & Treason.” He warned his friend “not to expect that your late foes in arms” would feel much urgency toward relief measures when Southerners clung to such canards as “the North began it.”

Prentis’s hard-line views gained full expression after the president of the former Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, was captured. “What is to be done with Jeff. Davis?” he mused in a five-page essay. He credited only the “law abiding instincts of our people” with the fact that Davis’s treason, a crime “of the most revolting magnitude,” had not yet been met with mob justice. He argued further that Davis ought to be held responsible for the barbarous treatment of Union soldiers in the “various prison pens of the South”; whether or not he knew of these violations of the laws of war, circumstantial evidence trumped any attempt to absolve him: Davis was like “the keeper of a menagerie of wild beasts” who had turned them loose to commit atrocities.

Prentis scoffed at the proposal to put Davis on trial in, of all places, Richmond, Virginia, where “there is no earthly chance of conviction.” Instead, “as more or less a prisoner of war,” he ought to be tried before a military tribunal. Even more incomprehensible were calls from some individuals and the press for a simple “acquittal.” This, Prentis declared, flew in the face of both human and divine justice and “inculcate[d] the atrocious sentiment that the greater a man[’s] crimes the less he should be punished for them.” Treason, the worst offense imaginable, demanded the “extreme penalty of the Law,” and neither legal technicalities, nor forum shopping, nor squeamishness about retributive justice should thwart this verdict.

The letters and essays of James Prentis are part of the Prentis Papers in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives collections of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here for a finding aid, selected scans and typescripts. For more Civil War collections, click here or search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.