They were late-night, improvised musical events that captured the romantic imaginations of nineteenth-century students, particularly those at Southern women’s colleges. At Bowling Green’s Potter College for Young Ladies (located where WKU’s Cherry Hall now stands), these “midnight serenades,” courtesy of the boys at Ogden College just down the hill, featured a group of admirers sneaking on campus to croon up at the windows such old-time standards as “Swanee River,” “On the Banks of the Wabash,” and “Home Sweet Home.” Even the rumor of a forthcoming performance would stir excitement among the girls and consternation among their live-in teachers, whose job it was to shoo the interlopers off the grounds.

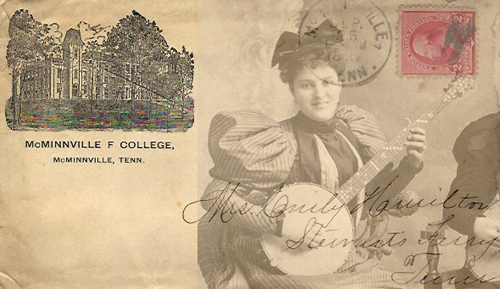

But at Cumberland Female College in McMinnville, Tennessee, serenades attracted more participants than just the parties to an exaggerated courtship ritual. While staying with her aunt Josephine and uncle Joseph P. Hamilton, a teacher at the college, young May Hamilton told her grandmother about the previous night’s music. “Just as I started to bed I thought I heard serenaders up at the college,” she wrote in a letter, “and so I went & sat down on the floor by the window to listen.” The performers, however, were not ardent young males but “the girls of the college. . . making sweet music” nearby for one of the professors and his family. His appearance at the door to thank the performers must have emboldened them, for the troupe then marched down to the Hamilton household. “One of the girls plays the banjo & several had harps,” wrote May, who woke up another boarder at the house so they could both enjoy the “lovely” melodies.

Luckily, the night’s entertainment was not over. The strains of more music came through the window, but the darkness concealed the identity of the players, who then proceeded up to the college. May learned the next morning that the group consisted of four or five African-American youths who “go around that way often up here.” So popular had they become, in fact, that the girl boarding at May’s house knew the group by the sound of their instruments, and even knew the horn player by name. The local custom, it seemed, was for everyone so inclined to reach out and say goodnight with a song.

May Hamilton’s letter is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.