Who wouldn’t have wanted to experience the artistic and cultural treasures of Europe in the company of Beulah Strong? Born in 1866, the Massachusetts native studied art in Paris, then joined the faculty at Bowling Green’s Potter College for Young Ladies, where she taught art from 1892-1901. After three years at Nashville’s Belmont College, she moved to Smith College, where she was an associate professor of art from 1907 until her retirement in 1923.

After retiring, Miss Strong moved to Florence, Italy but still kept in close touch with her friends in Bowling Green. Her holiday letter of December 2, 1933 showed how eagerly she had taken advantage of her proximity to Europe’s most charming destinations. “Without taking any very long or distant trips” over the past year, she wrote, “I have had a number of small and pleasant ones.” Small and pleasant indeed: there was the previous Christmas spent in Rome, “splendid and grand,” its vistas opened up by the cleaning up of the “mean streets.” There was a tour of northern Italy – Pavia, Brescia, Cremona, Mantua and Parma – which she made sure not to visit at Lent because the altar-pieces in the churches would be covered up. There was the great Franciscan monastery at La Verna, with its “precious” Della Robbia terracottas and “many picturesque nooks.” Then, three weeks exploring the museums of Germany, with excursions to the cathedral at Bamberg, the Bavarian resort town of Tegernsee, and other “lovely little cities.” And at home, there was gardening, concerts, and afternoons entertaining friends from the local expatriate American and English communities.

But as Depression and war loomed, ugliness was intruding upon all of this beauty. Of immediate concern was the financial squeeze that jeopardized Miss Strong’s desire to make another holiday trip to Rome. Prime Minister Benito Mussolini’s efforts to prop up the lira were colliding with President Franklin Roosevelt’s devaluation of the dollar as part of his economic recovery plan. For the time being, however, only FDR – “our dictator-president” – attracted Miss Strong’s ire for undercutting the purchasing power of her savings.

More unsettling were affairs in Germany. Upon entering, Miss Strong had been required to disclose her money holdings – “just how much I was taking in and it was checked up as I came out.” Even more ominous was the growing persecution of German Jews after Adolf Hitler’s seizure of dictatorial powers earlier that year. An elderly Jewish friend had asked Miss Strong to check on her family in Germany “and hear from their own lips how things were, as letters are censored, opened at the frontier.” Some of the family had begun to experience the effects of laws excluding Jews from professions and civil service positions “and as these Government places were for life with a pension at the end, few of them saved much.” Emigration, too, was increasingly difficult, given the restrictions on taking money out of Germany. Still, Miss Strong remained more suspicious of Roosevelt’s fiscal policies, hoping he “won’t try that scheme! We should have to crawl home with our tails between our legs.”

Back in August 1914, while touring Europe with her mother, Beulah Strong had barely managed to secure passage back to the United States at the outbreak of World War I. History seemed to repeat itself in 1940 when she returned again to the United States, leaving behind both the beauty and ugliness of her Italian sojourn.

Beulah Strong’s letter is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid and scan. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.

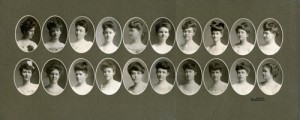

These twenty ladies comprised the Potter College for Young Ladies Class of 1903. To date we have identified Mamie Johnston, Maud Cole, Celeste Cuthbertson and Hallie Brite. As with many photographs in the WKU University Archives, we need your help to identify the remaining members of the class. A larger version of this image is available online at:

These twenty ladies comprised the Potter College for Young Ladies Class of 1903. To date we have identified Mamie Johnston, Maud Cole, Celeste Cuthbertson and Hallie Brite. As with many photographs in the WKU University Archives, we need your help to identify the remaining members of the class. A larger version of this image is available online at: