She was found in the privy. There were signs of a scuffle, during which she had been choked by a strong pair of hands, then stabbed in the neck and chest. The murder of Harriet Porter took place around midday, February 8, 1858, on the Allen County, Kentucky farm where she resided with husband Uriah, five children, and perhaps twenty enslaved persons.

As word spread, locals converged on the farm and tried to determine what had happened. Suspicion fell on one of the slaves, Jack, who was ultimately charged, found guilty, and hanged.

Jack, however, had implicated another slave, John, as his co-conspirator in the deed. A grand jury indicted John and he was likewise found guilty, but in April 1858 he successfully petitioned for a new trial. He claimed that not only was the jury’s verdict contrary to the evidence—the testimony of some of his fellow slaves had made clear that he could not have participated in the crime—but he had learned of Jack’s confession to “two gentlemen of high standing” that he, John, “had nothing in the world to do with the murder of Mrs. Porter.” Because of local prejudice and the notoriety of the case, John also asked for the trial to be moved to neighboring Warren County, and prayed that the court might give him a chance to “be saved from an unmerited and horrid Death” at the hands of the hangman.

The record assembled and forwarded to the Warren County Court documents a complex but meticulous effort to uncover the truth about John’s role in the murder. Interviewed by a Scottsville physician, Dr. Algernon S. Walker, John explained that he had performed his morning chores and cut oats in sight of the privy, and noticed nothing unusual. He went to the servants’ house for dinner, then out to the orchard, then to the shop to offer help in a wagon repair. At some point he thought he heard a commotion at the privy, but thought nothing of it.

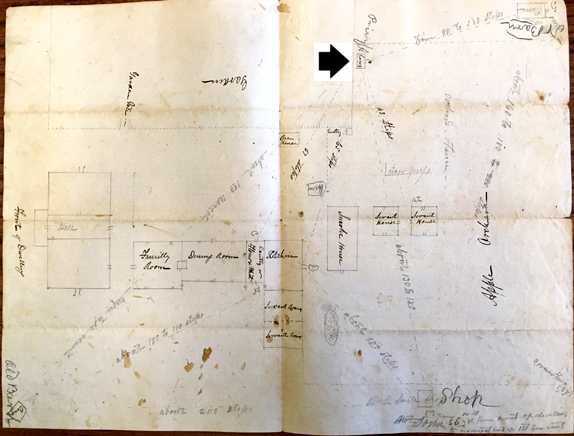

Unfortunately for John, the two gentlemen who had supposedly heard Jack’s confession declined to make oath to that effect, so circumstantial evidence became critical. Numerous other witnesses, both slave and free, gave testimony in an attempt to determine John’s movements and demeanor on the day of the murder. When was he at dinner? Who saw him there? Where was Jack during this time? In an effort to construct a timeline, a sketch of the farm buildings was prepared showing the distance, in steps, between privy, orchard, shop and servants’ quarters.

Instructions to the jury in the Warren County trial, at which prominent lawyer Henry Grider defended John, betrayed the difficulty of their task. Should they convict on the basis of Jack’s accusation alone, in the absence of other corroborating evidence? Should Jack’s story be discounted if it had been given in expectation of reward, or contained inconsistencies? And just how much circumstantial evidence was necessary to raise—or exclude—a reasonable doubt as to John’s guilt?

After considering all this, the jury reached a verdict. John was acquitted.

John’s case highlights a curious aspect of the institution of slavery. While he was chattel—“the property of Uriah Porter,” read the indictment—John was, for the purposes of criminal law, to be treated as a human being responsible for his actions. As one historian of slavery has observed, a lesser offense would have subjected John to swift “plantation justice,” but for a capital crime he was more likely to receive the same procedural protections as those given to accused free persons.

The record of John’s case is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here for a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.