A looming pandemic, its dangers made vivid by the closing of churches, schools and other places of assembly. A ramped-up campaign of “warning and advisory literature.” A frantic effort by federal and state authorities as well as local physicians and relief workers to suppress the spread of the disease, followed by some relaxing of quarantine restrictions.

Then, a series of “celebrations and similar festivities, during which all precautions and safeguards were thrown to the winds.” A spike in cases, and renewed calls to reinstate closures. But then, a vaccine, ready to be distributed to states and administered first to those most at risk.

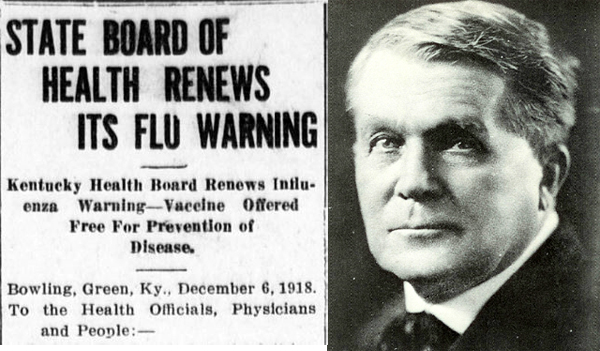

So read the summary of Dr. Joseph N. McCormack, Secretary of the Kentucky State Board of Health, published in newspapers in December 1918. The pandemic, of course, was influenza, and the super-spreader celebrations were the parties, parades and gatherings that marked the end of World War I.

The vaccine to which McCormack referred, one of many produced during the pandemic, had been developed by Dr. Edward C. Rosenow of the Mayo Foundation’s Division of Experimental Bacteriology. After testing it on the staff of his own institution and concluding it was safe, he offered it free to physicians and hospitals, as long as they would return questionnaires reporting on its use and results.

McCormack responded to Kentucky doctors who requested doses of the Rosenow vaccine with a letter outlining its ingredients, giving instructions (three inoculations, one week apart), and touting its successful use in the Army—and curiously, on policy holders of the Equitable Life Insurance Company and employees of Pittsburgh’s Homestead Steel Works. The Kentucky State Board, he advised, endorsed the vaccine for use “by every person in Kentucky who is not certain that he or she has recently had influenza.” McCormack’s colleague Dr. Lillian H. South, who had visited the Mayo Clinic to procure a half-million doses, had charge of distributing the vaccine from the State Board’s offices in Bowling Green.

Despite Dr. McCormack’s eminence—he is now regarded as one of the most influential public health figures in Kentucky’s history—his letter showed that vaccine development and testing was still in its infancy. For example, like other vaccines of the time, the Rosenow vaccine was made from what one historian has described as a “witches brew” of bacteria isolated from dead and living patients, “heat-killed,” and added to an injectable fluid (compare to today’s COVID-19 vaccines, which do not contain the virus). Vaccine studies, moreover, suffered from what our historian has termed selection bias, unequal exposure to risk, and inadequate data collection on outcomes. (Rosenow’s requests for responses to his questionnaire, in fact, appear to have been largely ignored).

The Rosenow vaccine was soon subjected to a somewhat more rigorous test involving the residents of a California asylum. While still lacking many of the methods employed in today’s clinical trials—double-blind studies, placebos, and informed consent of subjects, to name a few—this study found the vaccine to be ineffective. The confusion nevertheless brought a significant benefit, namely the initiation of a movement in the medical profession to devise proper standards for vaccine trials.

In the meantime, even Dr. McCormack understood that vaccines were not a panacea. In his announcement given to newspapers that December, he admonished flu-ravaged Kentuckians in now-familiar terms:

1. Keep away from all crowds of all kinds.

2. Keep out of the sick room and away from houses with sickness, unless your services are needed. Keep clean and wear a mask if you do go.

3. Cover your cough or sneeze and keep away from people who do not.

4. Keep away from dirty eating and soft drink houses.

5. Have and do little visiting until this epidemic is over.

Dr. Joseph N. McCormack’s letter to physicians about the Rosenow vaccine is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid and scan of the letter. For more of our collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.