In 1976, the appearance in humans of a previously unknown strain of swine flu virus prompted WKU history professor Dr. Carlton Jackson to begin a research project on the deadliest disease outbreak in the United States up to that time. For A Generation Remembers: Stories from the Flu, 1918, Dr. Jackson placed queries in newspapers across the country soliciting memories of the great influenza pandemic of 1918, which killed about 675,000 Americans. Although he didn’t achieve his goal of producing a book or article, his grim but fascinating research has been preserved.

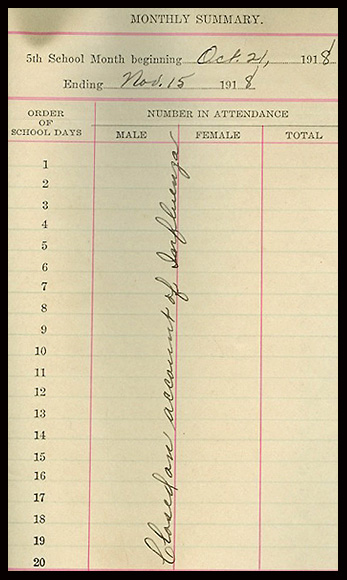

Dr. Jackson received letters and narratives from almost 450 people recalling their experience of the flu as it struck in 42 states and 9 foreign countries. In 1918, of course, all of the witnesses were young, but most remembered vividly the impact of the pandemic on their families, their neighbors and their communities. They remembered the savage symptoms: high fever, severe headache, chills, back and leg pain, pneumonia, and the blood that gushed from noses and lungs when the victim coughed. They remembered the closure of schools and businesses; the disease’s particular toll on pregnant women; the hasty, improvised funerals; the mass graves; and the apparent arbitrariness of infection and death. Some remembered being untouched by illness as others around them sickened and quickly died. “It was like a tornado,” wrote one respondent, “some houses will be blown away & the one next door will stand & that’s the way the flu went thru the country.”

Others remembered the often quirky and largely futile attempts to ward off infection: with whiskey, chewing tobacco, quinine, castor oil, formaldehyde, even green sour apples. More than one mentioned the use of asafoedita, a lump of plant-based resin carried in a bag around the neck, which would emit a smelly “gas cloud” thought to repel the flu “bug.” And should that “bug” attempt to attack from a different angle—say, by creeping up the legs—a spoonful of powdered sulphur in each shoe would raise a similar odorous defense. (Don’t laugh—it was hypothesized that this method may have actually helped by making it unwise for its stinky practitioner to mix in crowds, thereby avoiding infection from others.)

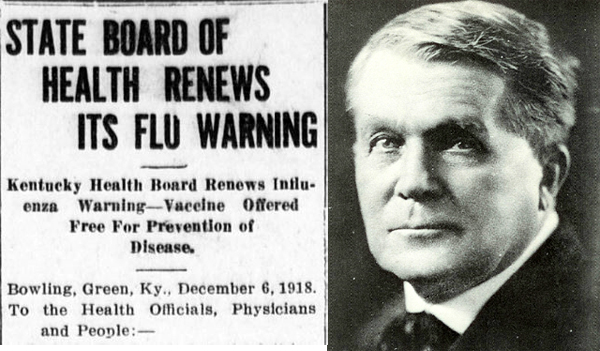

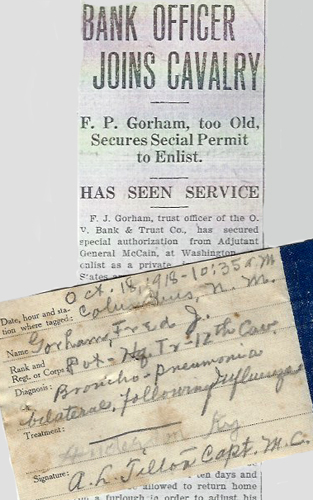

And speaking of crowded places, the flu exacted a terrible cost on the military, then still mobilized for World War I. Some 45,000 American servicemen succumbed, about two-thirds of those in stateside camps. At Camp Zachary Taylor in Louisville, wrote one respondent, doctors and chaplains were “buried under the demand for care.” He and other students at nearby theological seminaries were drafted to act as liaisons with soldiers’ parents. When told of a son’s dire condition, a mother could become indignant “and sometimes near hysterical” when denied entry to the ward to see her boy.

The price paid by servicemen also brought Dr. Jackson a memory from Bowling Green. William C. Lee was then a prep student at Ogden College. “One of my most vivid recollections,” he wrote, “was seeing large stacks of caskets” at the railroad station awaiting transfer between the main line of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad and the Memphis branch. Lee’s father, a railway postal employee, told him that the trains often had to add extra cars to carry remains back home to the soldiers’ families. And sometimes their escorts were not spared: during the train stops, soldiers—“the living ones, that is”—might drop in at the local canteen for food and coffee, only to suddenly collapse—“one of the first symptoms” of this deadly flu.

Letters to Carlton Jackson with a generation’s stories of the flu are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more collections about influenza, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.