It’s a slender, legal-sized ledger with a nicely marbled cover, but worn from use and with some of its pages missing. Its mid-nineteenth-century inscriptions appear to have been of little interest to a later custodian, who used its blank pages to doodle and trace comic strip frames. At some point (perhaps about 1930), it ended up in Bowling Green’s city dump, where it was retrieved by a schoolboy and given to the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections.

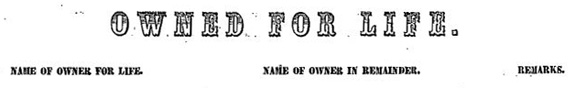

It’s a “Register of Slaves Owned for Life,” but the reference wasn’t to the life of the slave. Instead, it was a stark reminder that, because of their legal status as chattel, enslaved people were subject to often complex and arcane Anglo-Saxon laws governing personal property. Early Warren County court records show the frequent litigation that ensued when slaves were bought and sold, but also gifted, loaned out, mortgaged, divided up under estate settlements, and seized and sold for debt (or hidden away to avoid such seizures). Enslaved people were also devised by will, either outright or, for example, to a widow for life and then after her death to an ultimate beneficiary, often children—the “remaindermen” or “owners in remainder.”

It was this last arrangement that the Register of Slaves Owned for Life was meant to monitor. Since the owners in remainder had a future enforceable interest in the enslaved people, life estate owners were required to make an annual report to the county clerk of the names, sex and ages of slaves in their possession. We learn, therefore, that in 1855 Mrs. Mary Burford had life ownership of eight enslaved men and ten women, who were to pass to the heirs of the late J. A. Cooke on her death. Mrs. Burford, however, was free to sell her life interest in some or all of the slaves; she did so on at least two occasions, obliging the transferee to make subsequent reports.

In addition to an enslaved person’s name, age and sex, other descriptive information was commonly added, such as skin tone and physical characteristics or peculiarities. But while they were considered commodities, enslaved people were living commodities, their births, children and deaths adding fluidity to their value to life estate holders and remaindermen. They also performed duties that confounded their status as chattel and foretold the future: a life interest holder’s final report in April 1865 listed five enslaved men who were serving as volunteers in the Union Army.

Emancipation, of course, ended the need for records of property in people. For some of them, the break was clean, but (surprise!) the law occasionally dragged its heels. Witness the answer of the defendants in a suit brought in Barren County disputing the proceeds of a mortgage of three enslaved people. Two had earlier been sold, but the third, a woman? She was of no value, huffed the defendants, since she was “‘lying loose around’ under the idea that she is free.”

Click on the links to access finding aids (including a full-text scan of the Warren County Register of Slaves) for these collections. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.