Nineteenth-century Kentuckians commonly began their wills with a declaration of mental but not physical vigor. I, [name], being weak and sick in body but of perfect mind and memory, or some similar phrase, was the usual prelude to a disposition of assets upon death.

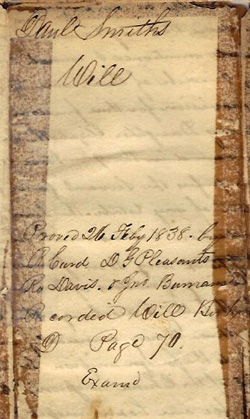

Daniel Smith displayed a slightly different attitude when he composed his will in 1836. Though the Warren County farmer would depart this earth less than two years later, he claimed to possess both “common understanding & memory” and to be “in my usual health.”

In his will, he hinted at his prosperity and directed that “what earthly goods it hath pleased God to bless me” – cattle, sheep, horses, mules, household furniture, money, notes and bank stock – be used for the support of his wife Mary and “our two afflicted children Anna & Robert Smith.” After the death of any two, the survivor was to receive $1500, then share the estate equally with three other sons and a daughter. Small bequests also went to foreign missions in China and Burma.

Smith’s instructions, however – all preceded with the phrase “It is my will and desire” – took up little more than half of his four-page testament. The rest dealt with property to which he gave equally careful thought: his enslaved servants.

Smith set up a staggered schedule for their emancipation. Moriah was to enjoy the rights of a “free white person” at the end of 1838, “provided she does not live within Ten miles of my family.” Peter was to be “released from bondage” at the end of 1841; both he and Moriah were to receive aid from Smith’s estate if they were unable to support themselves. Six others – Isaac, Peggy, Ellen, Jane, Charlotte and George – were to be freed between 1843 and 1850. Children of the enslaved servants were not to be free until age 25, but if any of their freed parents should “desire to emigrate to Liberia,” the children could accompany them.

While emancipation by will was not unusual, Smith’s directives starkly illustrated the primacy of property rights over human rights. In the case of Sam, an enslaved man who had “been accused of making some unwarrantable threats,” the promise of freedom at the end of 1848 would depend on his good behavior. Any further misconduct, Smith instructed, and “he must be separated from my Family and sold as a common Slave.” All of Smith’s enslaved servants, in fact, were subject to sale by his executors “up to the time at which they & each of them are to be free.”

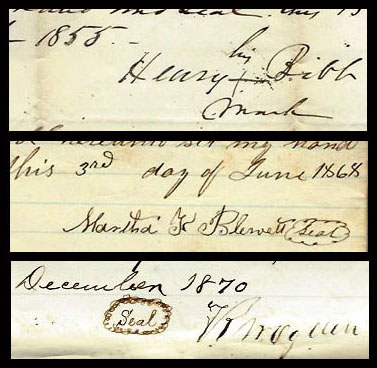

Smith’s control over his enslaved servants was most evident when it came to Moriah, due to be freed at the end of 1838. Learning that Moriah “is inclined to use too much strong drink, & disposed to dissipation,” he revoked her emancipation in an 1837 codicil to his will. Instead, she was to be hired out to “some good master who is Religious & pious” and who would treat her well and “furnish her with better & more comfortable clothes than common hired Servants is allowed.” Part of the payment for her hire was to be put aside for her maintenance – the portion to increase “as she gets of less value” – and the balance invested for her benefit, to be used “as she may need it” or disposed of on death “as she pleases.”

Daniel Smith’s will – a remarkable document that arguably recognized some humanity in his enslaved servants, yet deprived them of agency even as his own power extended beyond death – is part of a collection of early Warren County Court records in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library. A finding aid can be downloaded here. For more collections, search TopScholar and KenCat.