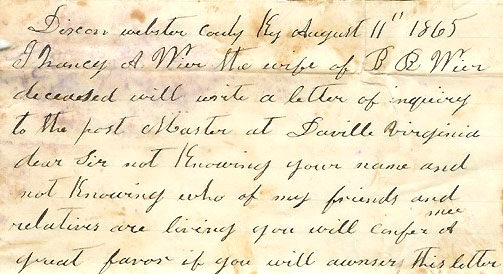

It was the plaintive appeal of a woman displaced by war. In 1865, Nancy Wier wrote from Webster County, Kentucky to the postmaster at Danville, Virginia. A native of the area, Nancy had lost touch with her family after the outbreak of hostilities. Her husband, a Confederate soldier, had been imprisoned at Camp Douglas, Illinois, where he died of smallpox. Left with four children, Nancy had been teaching school but “my troubles are very great,” she explained to the postmaster. “I wish to know who of my relatives and friends are living,” she wrote, naming her sisters, her “old father” and her brothers, who she hoped might come and “spend the last of their days with me.”

Fortunately, three years later Nancy had not only reestablished contact with her siblings, she had remarried and her children had begun lives of their own. Nevertheless, her mother’s radar was intact. “I can never get weaned from my children,” she wrote a sister. “Bettie lives 18 miles from me Sarah five Virginia two and a half William ten he often comes to see me they come as often as they can.” Equally strong was her desire to maintain contact with those lost to her during the war. She agreed with her brother that even “if we never can see each other we must try to keep up correspondence.” Having found out “who is living and dead,” she was determined not to loosen the ties again.

Nancy Wier’s letters and those of other family members are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives collections of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here and here to access finding aids. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.