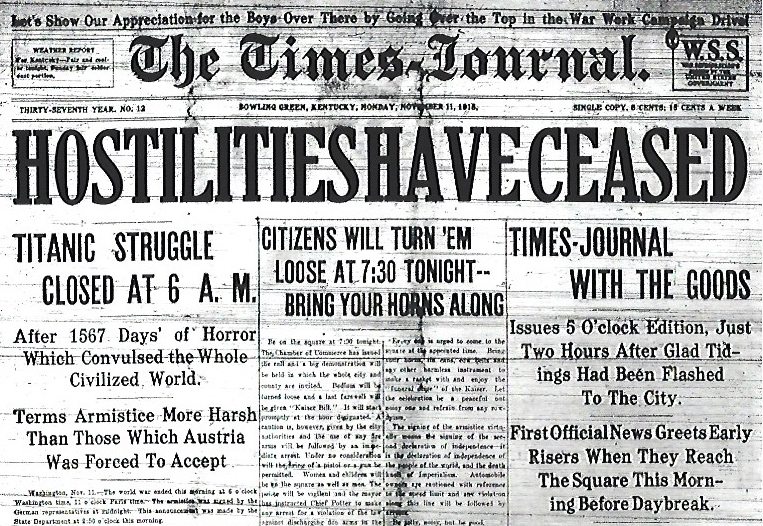

Seventy-five years ago today, on November 26, 1943, one of the greatest and least-known losses of Americans in a single naval incident took place when the troopship HMT Rohna sank in the Mediterranean Sea.

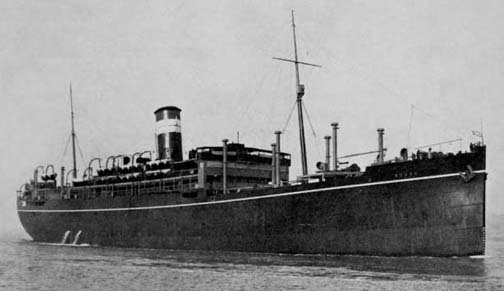

Built in 1926, the Rohna was a converted British cargo ship—“crummy and dirty,” remembered soldier Charles Finch—with an Indian crew and an Australian commander. Carrying 1,981 American troops, it was part of a convoy headed from North Africa to the China-India-Burma theater. Late in the afternoon, a German aerial attack sent the vessel to the bottom of a cold, rough sea. Of the 1,138 resulting deaths, 1,015 were American—only 162 less than the toll aboard the USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor.

The incident was quickly shrouded in secrecy. Survivors and families of the dead were told little about what had happened. Only with the passage of time and the declassification of military reports did the story become clearer. The 8,602-ton Rohna had perished in 30 minutes after a single German aircraft launched a new and terrifying weapon: an early “smart bomb,” propelled by a rocket engine and guided to its quarry by an operator via radio signal.

When WKU history professor Carlton Jackson set out to write a book about the Rohna disaster, he gathered letters, narratives and official testimonials from survivors, witnesses, and families of the victims. The stories he received were harrowing: of the fiery inferno ignited when the bomb slammed into the engine room, of men trapped below decks, of the ensuing chaos as the Rohna’s civilian crew abandoned their stations, of lifeboats that couldn’t be lowered because of rusted pulleys, of desperate men clambering down ropes to the sea or simply jumping, of rafts crashing down on the heads of men in the water, of German planes strafing overhead, and of the ordeal of injured survivors awaiting rescue for hours, clinging to debris or trying to remain afloat in heavy seas with only small inflatable lifebelts.

On board the nearby HMS Banfora, Abe Kadis remembered the Rohna with a hole blown completely through it, the screams of wounded men, and “heads bobbing in the water.” Nevertheless, the rest of the convoy was forced to sail on until it was safe for rescue ships to return. “I felt so alone and completely helpless,” remembered Charles Finch, who had gone over the side by rope. “There was now nothing in sight except the dead bodies that continued to bump into me from time to time.” The USS Pioneer eventually picked up Finch and many of the Rohna survivors. One of them, Private Henry Kuberski, spent weeks in hospital recovering from burns. “Hank,” read the telegram to his wife, had been only “slightly injured.”

Carlton Jackson’s research for his book Forgotten Tragedy: The Sinking of HMT Rohna (reissued as Allied Secret: The Sinking of HMT Rohna) is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more World War II collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.