The Folklife Archives is certainly no stranger to the supernatural, and while the rustling sheaves of onion-skin paper or sudden burst of cold air may find a culprit in the questionable HVAC system, there’s still something slightly sinister stirring inside the storage boxes.

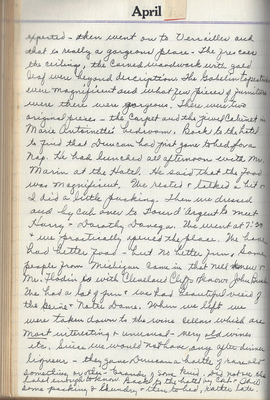

In January 1983 a student paper, written for an undergraduate folk studies class, was donated to the Folklife Archives. Titled “Hexing: Personal Experiences That Were Possibly ‘Hexing’ Episodes,” the essay came with an ominous warning, “CONTRIBUTOR’S NAME MUST NEVER BE USED.” The contents of the paper, a brief—but nonetheless thrilling—three pages, detail one woman’s experience with her slightly telekinetic powers.

To begin, the author describes the process of placing a hex on someone who has caused harm in some recognizable way. “The person that [is] doing the hexing has to balance on one leg—the left one, I think—and extend their left arm fully towards the person they wish to hex. The index and small fingers should also be extended, with the rest of the fingers made into a fist.” The channeling of pure rage and resentment towards the wrongdoer is also a critical step in performing a successful hex. The author is quick to point out, however, that while she rarely indulges her feelings of anger, the overwhelming sense of powerlessness and jealousy at several key moments during her adolescence were enough to justify a dabbling in witchcraft.

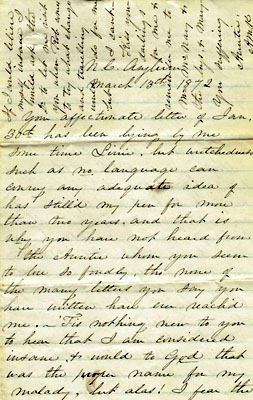

Illustration for the “The Thing on the Floor,” a short story found in the March 1938 issue of Weird Tales about a devious hypnotist.

The author runs through a laundry list of those who have mistreated her: the “extremely unfair” middle school teacher who suffered a broken ankle, the “very unfair” father who broke his wrist, the “babbling” woman who fell off a ski lift after stealing away the “good-looking and charming” ski-instructor, along with a host of other unsuspecting victims who fell prey to broken legs, broken arms, and burned houses at the hexing hand of one cruel mistress.

In her conclusion, the author confesses, “Whether this is a power that I possess or not, it used to frighten me and it is not something that I like to talk about. I have learned to live with it, however, and to control my feelings.” She leaves the reader with a final caveat,

“Well, those are the facts…it is up to you to decide for yourself what caused them.”

The paper itself (FA 228) is located within WKU’s Manuscripts and Folklife Archives. And while the archives cannot specifically condone the practice of black magic, it can provide you with more information on ghostly tales, haunted houses, and the occult. If you’re feeling brave enough, visit TopSCHOLAR or browse through KenCat, a searchable database, to explore manuscripts, photographs, and other non-book objects housed in the Department of Library Special Collections!

Post written by WKU Folk Studies graduate student Delainey Bowers