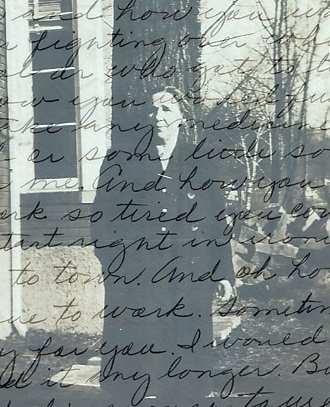

As we know from books like Code Girls, And If I Perish, and A Woman of No Importance, American women served in World War II out of duty and patriotism. But for some, the war also offered an opportunity for adventure and the chance to escape their small towns for a unique experience of the wider world. One of them was 19-year-old Dorenda Martin, who left her family’s farm in Smiths Grove, Kentucky in the summer of 1944 for a job in Washington, D.C.

In a letter to her parents, Dorenda described her work as a clerk-typist (“We are called Junior Clerks instead of Secretaries because the pay is less”) in the Washington Building, part of the city’s financial district anchored by the U.S. Treasury Building. Once there, however, she quickly found her racial prejudice put to the test. She was allowed time off work to attend an afternoon class to improve her typing skills, but found it populated mostly by African Americans (the boys were even called “Mr.,” she huffed) and switched to a morning class.

Near the Washington Building was the White House, where Dorenda and some coworkers chatted with an officer about getting a personal tour. President Roosevelt was out of town, they were told; as to the indefatigable Eleanor Roosevelt, laughed the officer, “didn’t any one know.” Dorenda also planned to visit the Pentagon, “a large war building” with its own shops as well as offices. She heard that the Duke of Windsor (whose Nazi sympathies were causing consternation in the intelligence community) had recently tried to enter, but didn’t have a pass so “he had some army officer to come help talk his way in.”

When not at work or sightseeing, however, Dorenda’s life revolved around “the Farms.” Located on the family estate of Robert E. Lee, Arlington Farms was a sprawling complex of temporary housing for female civil servants and service members. Residents were supplied with laundry, shopping, cafeteria and recreation facilities, and the lobby of each hall served as a rendezvous point with the servicemen who “just come out here and look around till they find a girl that looks to suit them.” Dorenda was more impressed with the military women: the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service, a branch of the Naval Reserve) who congregated in their blue and white uniforms for church services; and the WACs (Women’s Army Corps) who “were a lot of fun, & asked us to come to chow.” She was also intrigued by individuals like Juanita, a petite young woman from Puerto Rico; Vera, who had escaped the German occupation of Czechoslovakia; and a barefooted walker, who Dorenda “hollared” at to inquire where she was from. “I was expecting her to say Ky. because she said she didn’t wear shoes where she came from.”

After bringing her parents up to date with this lengthy letter, Dorenda concluded “I have a lot of fun here.” But duty called, and she “might not write for a month now.”

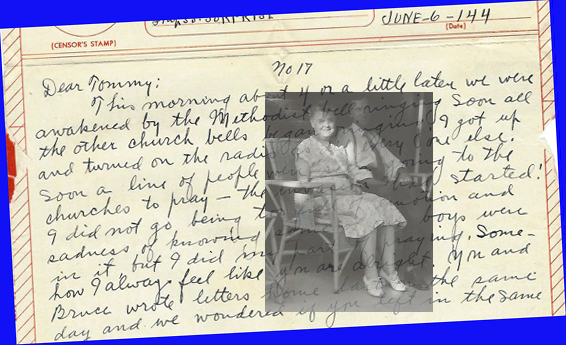

Dorenda Martin’s letter is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives collections of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here to access a finding aid and typescript. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.