For many travelers, the first step of a journey involves navigating a busy airport. During World War II, passengers faced additional stress when civilian air travel took a back seat to military priorities. This was doubly true for airline employees, who coped with challenges that went far beyond the ordinary joys of dealing with the public.

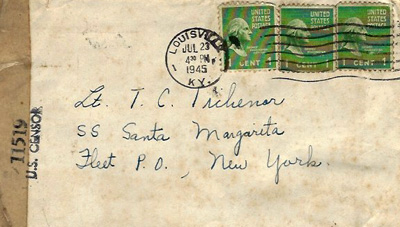

One such employee was 25-year-old Kate Hopkins, an American Airlines ticket agent in 1943 at Detroit’s City Airport. Her letters to boyfriend Thomas Tichenor, a Kentuckian serving in the Navy, give us a unique perspective on wartime air travel through the eyes of a clever and observant young woman.

Kate often found herself on the overnight shift–an assignment that, while wearying, gave her an opportunity to use her people-watching skills. After one such night, she wrote poignantly to Thomas about “the little sailor and his girl who sat locked in each others arms for a full forty minutes before his flight left, while his mother very quietly sat beside him, waiting to bid him good-by; about the little girl–she couldn’t have been much more than nineteen–who was going out alone to meet her husband, a Ferry pilot, in Spokane–and her family who came to see her off.” When the flight was announced, “her Father said ‘Well Ruthie–’ with all the pride and eloquence and love that only a Father could put into those two words, because what else could he say?”

Ferry pilots–members of the Air Transport Command, largely made up of civilians who flew aircraft from manufacturing plants to training facilities and ports for shipment overseas–were frequent airport patrons. Some of them, Kate observed, “are nice–others tough–some, surprisingly young and all very interesting.” One of them “came in last nite with an enormous plush Easter bunny–its long white ears protruding from a paper sack–He’d brought it back from Wilmington for his little girl.”

Kate grew accustomed to watching irritated Ferry pilots call the nearby base to complain when their ground transportation was not waiting. On other occasions, she became the object of customer ire. Determining that a passenger was too drunk to fly, she feared “he was going to hit me” when she declined to ticket him. She “finally eased him away from the counter” by inviting him to spend his unscheduled six-hour layover trying “some black coffee at the airport restaurant–that I knew was vile enough to cure or kill him.”

On still other occasions, the drama escalated. In the middle of one night, Kate received a message asking to have a cab waiting for an incoming flight “to take a Lieutenant and his eleven day old premature baby to Ann Arbor.” To her disgust, she could find no driver interested in the life-and-death mission unless they could also find a paying fare for the 40-mile return trip. As negotiations continued, the plane landed and “the captain himself escorted the Lieutenant and the baby, which he was carrying in a cardboard carton not much larger than a shoe box, to the cab.” The captain also grew furious with the cab driver, “especially when he’d flown at 2,000 feet all the way from Buffalo because every time he went higher the baby turned blue. . . . We finally got things arranged,” Kate reported, “to no one’s satisfaction.”

More often than not, however, Kate maintained her equilibrium. After checking in a line of difficult customers, she ticketed a young corporal who “was on an emergency furlough trying to get to San Francisco to see his six months old son who he’d never seen.” The baby was sick, as was his wife, exhausted from trying to run their ranch and summer camp by herself. But the soldier never lost his smile, and “was such a big person about it all,” wrote Kate, “that I felt awfully silly after all the minor irritations I’d had that day.”

Kate’s letters are part of the Tichenor Collection, housed in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. Travel through our other collections (and have mercy on the person “behind the counter”) by searching TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.