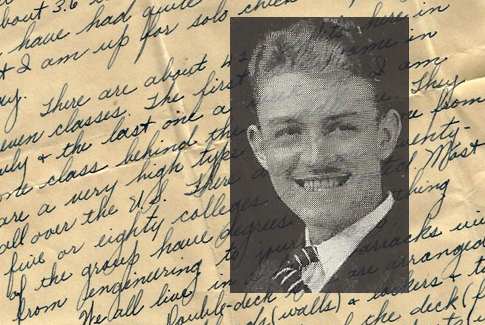

From his WKU credentials – Bachelor of Science (Biology), Chemistry-Physics Club, Band and Dramatic Clubs, Drum Major, and manager/second tenor in the Men’s Glee Club – it might have been easy to guess where Bardstown native John William Beam was headed next: perhaps to a high school to teach science and advise students in extracurricular musical and theater activities.

But “Billy,” as he was known, followed two of his brothers into military service. Where his older siblings had answered the call during World War I, however, 22-year-old Billy joined the U.S. Navy after graduating in 1935. He entered the new aviation cadet training program at the Naval Air Station at Pensacola, Florida, the site of heightened activity in the face of increasing world tensions. Billy’s letter to WKU friend Tom Tichenor, who was working on an article about him for the College Heights Herald, offers a glimpse into the peacetime military as it sought to enlarge, modernize, and prepare for any contingency during the ongoing debate over America’s role in international affairs.

Pensacola Air Station covered “several thousand acres,” Billy wrote, and housed 200 officers, 1,200 enlisted men and 1,000 civilian workers. One of about 425 cadets in seven classes, Billy described a “very high type bunch” representing more than 75 colleges across the country. Everyone resided in a six-winged barracks, making sure to keep beds made and lockers arranged with military precision. Billy was intent upon learning the prescribed vocabulary: walls were bulkheads, windows were ports, upstairs was topsides, floors were decks. “The time is screwy but when you get to 12 o’clock keep on going till 2400.” The cadets’ mandate was simple: “We have to look Navy, act Navy & talk Navy,” he wrote.

Billy outlined the day’s routine, from waking up at 0600 to taps at 2200. Groups of men alternated between squadron and ground school, where Billy had earned distinction in seven completed courses. Flight training was a five-step, 350-hour regimen designed to make them pilots in about a year’s time. Beginning with seaplanes, they moved to land planes, then to observation ships (“Here we get all formation flying, radio communication, navigation etc.”) to “big flying patrol boats,” and finally to “fast single seated fighters” where they learned “dog fighting, gunnery, bombing & everything else.” As aviation cadets, Billy and his mates were given the status of officers outside of working hours, enjoying free shows, Friday night dances, and a choice of recreation on their Saturdays off. And finally, “we get our wings & go to the fleet for three years & take our place alongside regular naval officers.”

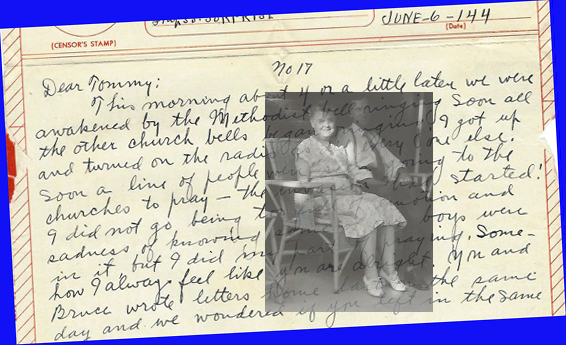

“Billy Beam Enjoys Navy,” headlined his friend Tom’s article in the February 21, 1936 Herald. But like that of too many young aviators, Billy’s story ended tragically. He died on November 17, 1938 in a plane crash, ironically, at Pearl Harbor, where his country’s next war would begin.

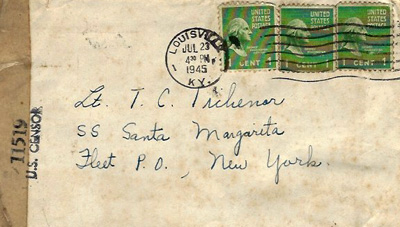

Billy Beam’s letter to classmate Tom Tichenor is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.