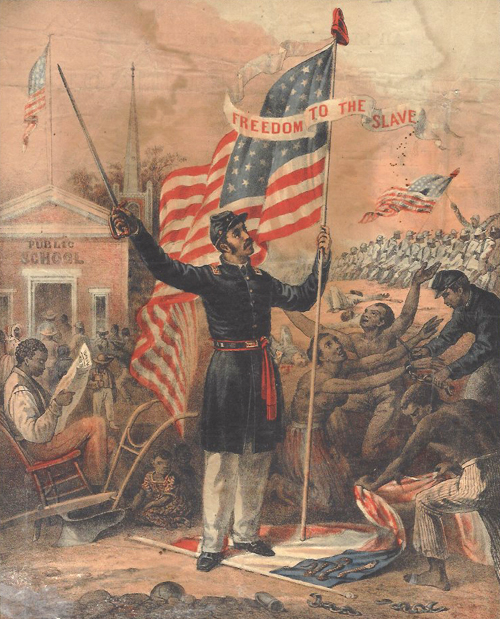

The Juneteenth celebration has its origins in the announcement delivered on June 19, 1865 by Union troops at Galveston, Texas, that “all slaves are free.” The Confederacy’s surrender the previous April had finally put the U.S. Army in a position to enforce President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which had taken effect on January 1, 1863.

In Texas and elsewhere, according to historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Emancipation “wasn’t exactly instant magic.” News traveled slowly, and sometimes those “who acted on the news did so at their peril.” After 1863, nearly 200,000 African Americans enlisted in the Union Army, and others took risky steps to establish (in the words of Juneteenth.com) “a heretofore non-existent status.”

Whites could be rather flummoxed by their former slaves’ embrace of emancipation. Shortly before the war ended, Sallie Knott observed that “Negro troops” had come to Lebanon, Kentucky to recruit. “They have already induced many to go,” she wrote in her diary, given that “their families are free as soon as they enter the army.” A Southern sympathizer, Sallie was nevertheless amused at the travails of a white neighbor whose slaves had all decamped. “The Madam is cooking herself!” she snickered. “There is a little good mingled with all this evil!” A month earlier, she had heard from her stepfather in Warren County that an enslaved member of his household had the temerity to ask “for wages! Papa told him he’d not give his own servant [sic] wages,” but would graciously give him Saturdays off. “I should not be surprised,” wrote Sallie, to hear of the “servant’s” early departure. Similarly, in Sherman, Texas, Patience Smith wrote to acknowledge the first letter received from her sister Emily in Tennessee “since the war broke up.” She seemed even more disoriented by the absence of enslaved labor. Her brother Burrell, she complained, “has not a negro on his land,” and his wife and daughter were stuck with all the work!

We have blogged before about the post-Emancipation odyssey of a young woman named Sophia, who for more than two decades was the mistress, housekeeper, and companion of Richard Vance, an Army officer from Warren County, Kentucky. Vance first met Sophia in 1867 at his military station in Little Rock, Arkansas and learned her story. When Emancipation came, she was still a young girl, and the rest of her enslaved family had already been sent away by their master to keep them from falling into the hands of the “hated yankees.” Sophia remained in a condition of “absolute slavery” until early 1866, when local African Americans learned of their freedom “through the instrumentalities of the Freedmen’s Bureau” and “were enabled through the same agency to take advantage of that fact.” Carrying only a bundle of ragged clothes, Sophia finally left. Twenty years later, she enjoyed a reunion with her long-lost brother and sisters in Texas. She found them prosperous, the owners of “farms, horses, cows, hogs, orchards, bees and all the paraphernalia of thrifty cotton growers. This is remarkable,” wrote Vance, who had helped her locate them, “seeing that only a couple of decades since they were slaves, uneducated, pennyless, and surrounded by a hostile population.”

Click on the links to access finding aids for these collections in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.