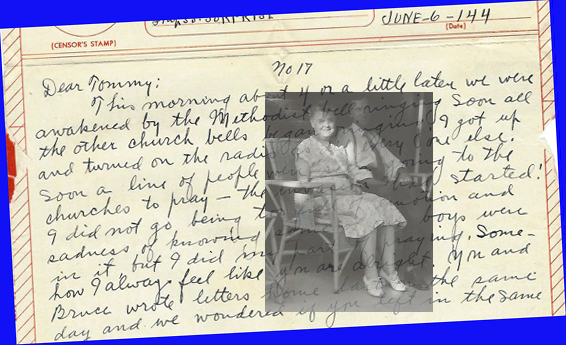

Everyone knew something big was coming – just not when or where – but on D-Day, June 6, 1944, the mystery was solved. As soon as she heard the news that morning in Calhoun, Kentucky, David Ellen Tichenor penned a letter to her son Thomas, then serving as a convoy communications officer with the U.S. Navy. In short letters (her V-Mail stationery limited her to one page) she relayed something of the predicament of ordinary people: the “majority in the middle,” in the words of philosopher Eric Hoffer, over whose heads “the best and the worst” so often clash to make history.

On the morning of D-Day, “about 4 or a little later,” she wrote, “we were awakened by the Methodist bell ringing. [S]oon all the other church bells began ringing. I got up and turned on the radio as did every one else. Soon a line of people were seen going to the churches to pray – the invasion had started!” – but she had stayed home, “being too full of emotion and sadness of knowing some of our boys were in it, but I did my part of praying.”

With the outcome still uncertain, there were only ordinary things to talk about. David Ellen reported that she and Thomas’s father had recently spent a day visiting family in Bowling Green (she was a niece of WKU’s first president Henry Hardin Cherry). Upon their return to Calhoun, they found that a generous rain had revived their beloved garden. “In fact it there had been quite a storm.” Everything, however, was “fresh and pretty.”

Six days later, wrote David Ellen, everyone was still glued to their radios, but “the invasion seems to be going along O.K.” Nevertheless, some of the Calhoun boys were “thought to be in it and their mothers are frantic. What a mess the world is in.” Mr. Tichenor was gathering “big luschious” cherries from their tree, an old one that would probably expire after “making its ‘war effort.’” Two days later: “The first ripe tomato to-day!”

Almost three weeks into the invasion, local mothers were still feeling the aftershocks. One of them came by David Ellen’s home crying because her son hadn’t received any of her letters (“Of course she writes all the time”) and was worried that something was wrong at home. For another, it was worse. “Alma” was “almost crazy,” she wrote, having received word that her son had been missing in action over France since D-Day. With so many boys being killed, the July 4th holiday was “the quietest day I have ever known around here.”

But still, ordinary life and hopes populated David Ellen’s thoughts: a lack of rain for the garden, a new veterans bill promising servicemen a college education, local marriages and babies, and especially her postwar plans for her son. Although the world was “a mess,” she didn’t think for a moment that it would stay that way. “I like your idea,” she told him, “of going to school a year when the war is over and getting your masters degree and a place in a college. Bowling Green would be a nice place.”

These are some of many World War II letters in the Tichenor Collection, held in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here for a finding aid. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.