Even though you feel you’re dying for the first, and dying from the second, the two worst afflictions in the world have to be homesickness and seasickness. When, as a child, Martha “Mattie” Spangler left her birthplace in Owen County, Kentucky to move with her family to Covington, it’s uncertain whether she felt pangs for her old home. In 1878, however, when 16-year old Mattie set out for boarding school at Hamilton College in Lexington, she keenly felt the loss of family and familiar surroundings.

Hamilton College was a typical 19th-century female school. The president, John T. Patterson, ruled the roost, and the young women were severely restricted in their activities and movements. Although she made friends and enjoyed the company of her roommates, Mattie watched wistfully when some of the students obtained permission to visit their own homes or those of friends on weekends. Trips to church or to shop downtown were limited to small groups and were chaperoned by Patterson or one of the female teachers. Beset by waves of homesickness and the “blues,” Mattie dreaded Mondays, rejoiced when Saturdays arrived, and counted down the days until she could go home for Christmas.

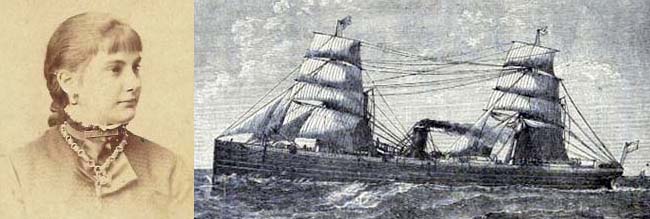

All the more surprising then, was Mattie’s departure in fall 1879 to attend another boarding school an ocean – and a world – away in Orléans, France. Enrolled at the “Pension Clavel” (shades of Villette!), she arrived after a Channel crossing from Southampton, England. Her trans-Atlantic journey had been on the steamship Oder, a German vessel that made regular crossings between New York and Bremen via Southampton.

It was aboard the Oder that Mattie had her experience – once removed, fortunately – with seasickness. She was apparently travelling with one Etienne Quetin, a Covington, Kentucky teacher of French, his wife, his son Alex, and “Mary,” possibly another member of their household. Then it hit. “Mary & Allie are as sick as dogs,” wrote Mattie in her journal, before noting (in the smug manner of the spared) that she felt fine and had a good appetite. She was rather annoyed, however, when queasy Mary claimed the bottom berth in their stateroom and left her with the top bunk.

The Oder’s support system for coping with mal de mer was pretty simple. Each berth, Mattie noted, “has a little vomiting can hooked on its side.” Though not needing it for its primary purpose, she was not above using it for an occasional expectoration. And that is where she got even, to her secret mirth, with bottom-bunk Mary. “As I went to get up in the morning,” she recorded, “I knocked my can, which was full of spit, right down on Mary’s head. When I found out where my poor little can had landed I lay back in my berth and laughed until the ship fairly shook.”

Mattie was not laughing, however, when a “funny fellow” on board, an artist, began surreptitiously sketching her as she gazed out at the sea. After rebuffing her plea to erase his work, he shared a “splendid” remedy for seasickness. “It is to swallow a chunk of salt pork with a string tied to it and pull it up again,” she recorded. “He believes in this which shows what a big ‘goose’ he is.” No mention of whether Mattie’s appetite survived this bit of advice.

Mattie Spangler’s journals detailing the ups and downs of her boarding school education have been recently donated to the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. A finding aid can be downloaded here. To read more about Mattie later in life, click here. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.