It was mid-April 1862, and word had reached Greensburg, Kentucky of the great battle at Shiloh. Native son Edward Henry Hobson had commanded the 13th Kentucky Infantry through what he would mourn as “a terrible affair,” and his brother-in-law Archie Lewis was relieved to hear that he had survived. Back home, Hobson’s wife Kate had just given birth, in Lewis’s words, to “a good ‘Union daughter.’”

Throughout the war, correspondents had faithfully kept Hobson apprised of news from Greensburg, where both Union and Confederate supporters uneasily coexisted and waited for word of their side’s fortunes. Initial reports from Shiloh were sketchy. Friend Samuel Spencer wrote that “the papers give very meager accounts of the matter except that it was the most deadly strife that was ever seen or fought on this continent.” An Army surgeon who had just returned on sick leave reported “various and conflicting rumors in relation to the matter” and was besieged with townspeople seeking information. A niece described the sad sight of “old gray haired men, standing around the P.O. door evening after evening, anxiously awaiting the arrival of the mail, and when the papers are read, eagerly listening to, and catching every word, if perchance they may hear some tidings concerning absent loved ones.”

The news vacuum left room for bluster and misinformation, and secessionists took advantage. Immediately after Shiloh, Archie Lewis assured Hobson, things remained fairly quiet in Greensburg “except the gass that is let off by the Secesh occasionally.” Soon, however, details of the battle began to emerge, both from official reports and from local boys who had borne witness. Sam Spencer told Hobson of his pride in the “Gallant 13th” and his relief that the “conflicting rumors and flying reports first received” about its heavy casualties had proven to be exaggerated. As the Union’s victory in the battle became more evident, Southern sympathizers who attempted to “preach Secesh on the corners of the street” were attracting smaller and smaller audiences. Ringleaders, however, persisted with their own version of events—“still trying to galvanize life into the thing,” remarked Spencer, “by lying and misrepresentation,” waving letters from the South “giving the most cheering account of the Grand Army of Beauregard and the Great victory” at Shiloh, and telling tales of Northern troops “now whipped to death” and falling back in panic. “This is but a small specimen of the Gulliver’s tales that some great men now tell the people,” Spencer complained, “and this is the food that they live on.” But, declared this passionate Union man, “a day of rec[k]oning is coming.”

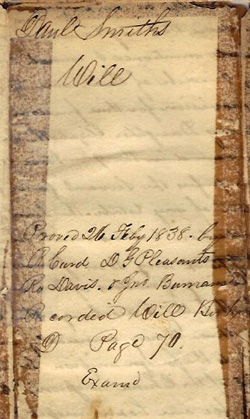

Edward Henry Hobson’s correspondence, which vividly describes the Civil War tensions that afflicted Greensburg and Green County, Kentucky, is part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here for a finding aid. Click here to browse our other Civil War collections, or search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.