For most of us, our most-deplored photo (next to our driver’s license) is the one on our passport. But it wasn’t until late 1914 that Americans were required to include a photographic likeness with their passport applications.

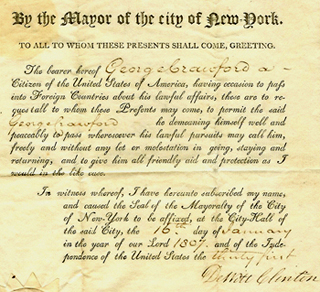

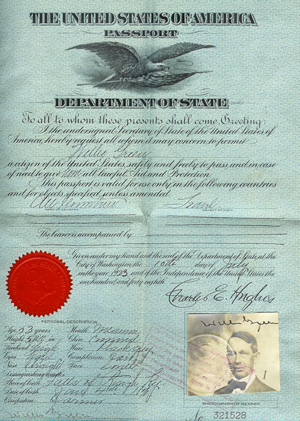

Earlier passports might simply state the holder’s name, as did the 1807 passport of George Crawford, signed by New York mayor DeWitt Clinton. Or the document might give notice of the age and physical attributes of its bearer. For example, the 1863 diplomatic passport of Bowling Green lawyer Warner L. Underwood described his high forehead, blue eyes, prominent nose, “ordinary” mouth and chin, round face, and “florid” complexion. George Harris’s August 1914 passport was for a man with a medium forehead, large nose, dark complexion, and dimpled chin. Although it included her photo, the 1919 passport of WKU teacher Elizabeth Woods also noted her medium nose and mouth, round chin, and oval face. Like Underwood’s, her passport was not the pocket-sized book we use today, although at 8X12 inches it could be folded in quarters and kept in a cardboard cover, like that of Grayson County merchant Willis Green.

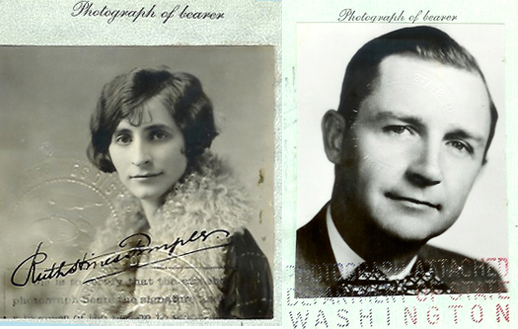

What gives modern passport photos their charm, of course, is that mug-shot quality (a “neutral facial expression and both eyes open” is the rule). But earlier specimens weren’t quite so uniformly dreadful. From the flapper-era glory of Ruth Hines Temple’s 1926 photo, to the Cold War-era gaze on Congressman Frank Chelf’s 1959 passport (“not valid” for travel in Hungary, Cuba, etc.), these photos allowed a little of the bearer’s personality to shine through.

Click on the links to access finding aids for the collections containing the passports of these traveling Kentuckians, part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives holdings of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. For more, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.