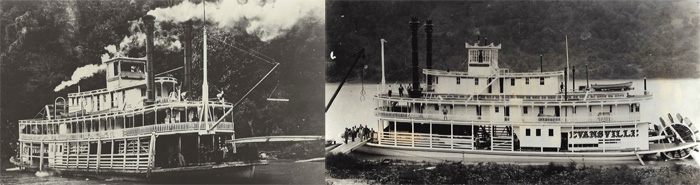

“The Eighth Wonder of the World.” It was a title the steamboat Evansville shared with her sister vessel, Bowling Green. Built in 1880, she carried passengers, tourists, livestock, farm produce and other cargo between the two cities until she was lost to fire in 1931.

It was a tricky business for the 30-foot wide by 120-foot long Evansville to squeeze her bulk through the locks and dams of the little Green and Barren Rivers. Departing Bowling Green for the return trip to Evansville required a “roundtoo,” a maneuver in which she would back down the river from the wharf into a chute at the foot of Wilkerson Island, then rely on the current to help swing her around and point her in the right direction. Steamboat engineer and historian Courtney Ellis recalled a nail-biter as the Evansville scraped up mud from the river’s edge while barely avoiding the limestone outcroppings on shore.

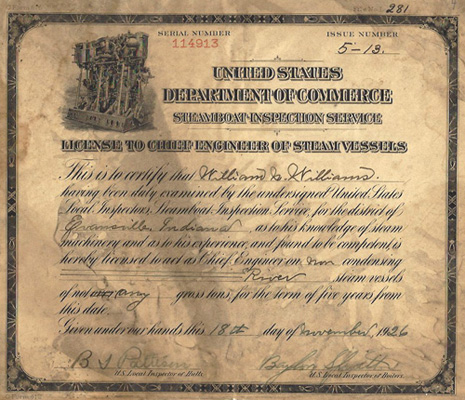

It was no surprise, then, that the captains, pilots and crew of the Evansville were some of the most skilled of their profession. Among them were Captain Richard T. Williams (1833-1912) and his five sons. The middle son, William, was in command of the Evansville on June 6, 1917, when he faced a sudden and deadly threat to the safety of his vessel and its passengers.

The Evansville had just passed Mining City, between Rochester and Morgantown on the Green River in Butler County, when the crew first spotted the dark funnel cloud in the distance. Williams’ nephew, serving onboard as a clerk, rushed to the captain’s quarters to warn of the approaching tornado. Realizing that his craft was no match for the storm, Williams ordered the throttle opened to “full steam ahead.” His only chance was to reach a nearby abandoned ferry, where the high bluffs there might afford some shelter.

The Evansville made it, and Williams ordered her tied up to a sturdy oak tree standing under the bluff. The thick manila rope – the “best money could buy,” for emergencies only – was handled by a crew member adept at managing the slack to keep the mooring post from being yanked out of the deck. The engines were set to “come ahead.”

When the tornado crossed the river about a half mile away, passengers watched in amazement as it “boiled the river almost dry.” Some insisted they could see startled fish flopping near the bottom and on the banks. The Evansville was driven backwards by the whirlwind, but its engines countered the force and the deckhand held its mooring line taut. A limb broke off the oak tree to which it was tethered, shot through the window of the pilot house, and narrowly missed the pilot in his high perch.

Then, almost as quickly as the water had been sucked out, the river “knitted back together” and the Evansville was safe. The tornado went on to wreak havoc on land – at Reid’s Ferry, it was said, it swept up a baby and laid it down a short distance away not only unharmed but laughing. If the passengers aboard the Evansville weren’t laughing, they were at least grateful to have survived the ordeal, thanks to Captain Williams and his crew.

This account of the Evansville’s bout with a tornado is part of the James R. Hines Collection in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here for a finding aid, selected scans from the collection, and a typescript. The photographs of the Evansville are part of our spectacular collection of steamboat photographs in the Courtney Ellis Collection. For more collections, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.