Twice a year, Dr. Charles Henry Webb of Princeton, Kentucky visited his mother in Lexington. In October, 1844 his wife was ill and unable to accompany him, so he departed with only their four daughters and a few servants. After leaving the two older daughters at boarding school in Lexington, Dr. Webb and his younger daughters, 11-year-old Nancy (“Nannie”) and 9-year-old Cassandra (“Cannie”) boarded the steamboat Lucy Walker for the journey home.

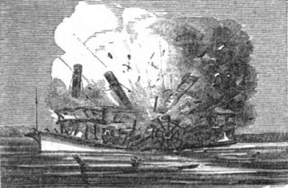

Near New Albany, Indiana, disaster struck. The Lucy Walker‘s boilers exploded, and she burst into flames and began to sink. Hurled into the air by the blast, Dr. Webb landed on a piece of floating wreckage. He was taken on board another boat with burns and a gruesome wound to the throat. A rescuer pulled Nannie out of the water when he noticed her hair floating on the surface, but Cannie drowned. No one knew what became of the servants.

Dr. Webb’s brother-in-law, George Washington Williams, rushed to New Albany to find him in the care of two doctors and some kind local citizens, but unfortunately, Webb soon died. In two letters to his wife Winifred, Williams mournfully described what he had learned about the accident, the sufferings of the victims, and the arrangements he made to preserve the bodies of his dead family members pending burial back in Princeton.

As it turned out, Dr. Webb’s wife had been ill because she was in the early stages of pregnancy. The following spring, she bore a daughter and named her Cassandra after the child’s dead sister.

George Williams’ letters, and the reminiscences of a descendant, are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives collections of WKU’s Special Collections Library. Together, they give a vivid account of the effect on a Kentucky family of the Lucy Walker disaster, one of the deadliest in U. S. history. Click here to download a finding aid. For more collections on steamboating, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.