Early in the 1900s, the crack of shotguns could be heard around the Bowling Green home of George and Anna Hobson. Used for storing Confederate munitions during the Civil War, the property (now known as Riverview at Hobson Grove) was home to a trapshooting operation, and its star was the Hobsons’ young daughter, George Anna.

Born in 1907, George Anna moved to Riverview with her family in 1912. Under her father’s tutelage, she quickly made a name for herself in the sport of trapshooting. At the 1920 State Fair Gun Club Tournament in Nashville, onlookers marveled at the “stellar gunning” of this “dainty 12-year-old miss,” who bested her own father when she broke 76 out of 100 targets.

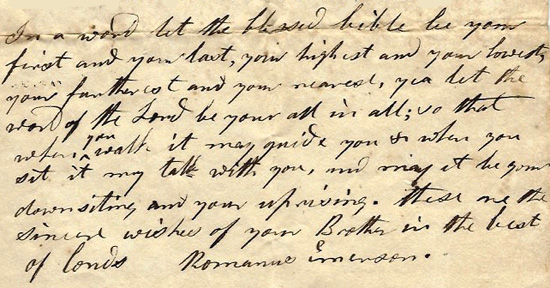

At age 16, George Anna, now a three-time women’s champion of the Kentucky Trapshooters League, took the national crown at the Amateur Trapshooting Association championship in Vandalia, Ohio. Congratulatory letters came from gun and ammunition manufacturers looking to capitalize on their part in her achievement, including the Western Cartridge Company and du Pont’s “Sporting Powder” division. George Anna’s use of an Ithaca Gun Company trap gun to win the national title prompted a request for a photograph to use in the firm’s advertising. “When you pose please get one from each side, first showing you lined up ready to shoot with your face towards the camera, then turn half way around and pose with the gun stock nearest the camera,” instructed the company vice president.

While profuse in their praise, some of her admirers couldn’t help looking at George Anna’s skills through the lens of gender. Complimenting her photo in Sportsmen’s Review, the editor of Outdoors South remarked, “I think you look awfully cute in knickers.” An observer sent her some snapshots taken at the national competition–“without your knowledge,” he wrote, “but thought you might like to have them as evidence of your graceful poise, even though you are under the strain of competition.”

Letters and other material relating to George Anna Hobson’s trapshooting career are part of the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Department of Library Special Collections. Click here to access a finding aid. For more on the Hobson family, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.