One spring afternoon in 1880, Matilda Stevens stopped by the Bowling Green home of her friend Hallie Thomas Hines. Mrs. Stevens, a local teacher of “marked individuality,” had been thinking about starting a club. Some of the city’s more prominent gentlemen had recently formed their own group, the XV Club, to discuss the cultural and political topics of the day over a hearty supper. Mrs. Stevens believed the women ought to have a club too; unlike the men, however, she thought it unseemly to use the device of a meal to bring such a knowledge-hungry group together. There should be no refreshments.

The result was the Ladies’ Literary Club, organized in March 1880 with 12 members and now recognized as the oldest club of its kind in Bowling Green. Over the decades, members have met twice monthly to study countless topics in literature, culture and history: Mozart, Mary Queen of Scots, Japanese religion, the Bible in literature, Chinese emigration, evolution, precious gems, English poets, and assorted book reviews, to name just a few.

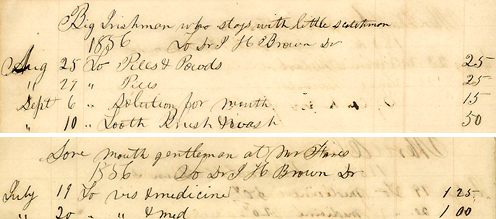

As the club minutes show, preparation was extensive, discussion was lively, and presenters were talented and intellectually curious. In the early years, several teachers from Potter College for Young Ladies were among the more formidable members. Giving “an elaborate historical talk” at the February 1, 1898 meeting, Gertrude Anderson “told the Club how Bismarck had put Germany in the saddle, taught her to hold the reins and ride triumphantly.” On February 15 her colleague, Mrs. M. E. Shelburne, “in her usual comprehensive style” gave the club “a most entertaining paper on the great German pessimist Schopenhauer. She seemed to take especial delight in airing his views on woman and her shortcomings. But,” the minutes continued, “the 19th century Club woman is too optimistic in her views to be depressed by such effete ideas.”

The Ladies’ Literary Club Collection, which includes minute books, correspondence and historical sketches, can be viewed in WKU’s Special Collections Library. Click here to download a finding aid. For collections on other local clubs and organizations, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.