Edmonson County, Kentucky’s story begins on January 12, 1825, when it was created from land carved out of surrounding Grayson, Hart and Warren counties. By May 1825, as prescribed in the enabling statute, the county court had gone to work on the nuts and bolts of infrastructure, finance, and law enforcement, and its order book, held in the Manuscripts & Folklife Archives of WKU’s Special Collections Library, tells that story in detail.

The book’s first entries document the appointment of constables, tax commissioners and a jailer, after which the court turned to locating the “permanent seat of justice.” A panel of commissioners recommended that the county seat be established on a 100-acre tract donated by patentees Joseph R. Underwood and Stephen T. Logan “on Green river and immediately above the mouth of big Beaver dam creek.” The town was “to be called and known by the name of Brownville [sic] in Honour of Genl. Jacob Brown who distinguished himself during the late war with Great Britain” – not the Revolutionary War but the War of 1812, in which many Kentuckians served. (Brownsville with an “s” was established in 1828 under legislation authorizing a town trustee-style of government.)

The county court itself needed a place to conduct business, so it enlisted one John Rountree to provide a two-story house with “a Bench for the Court to sit on also a bench for the Lawyers and a bar and Jury Benches,” and two jury rooms upstairs. A detailed plan for the county clerk’s office on the public square covered two pages: 25 by 14 feet, made of brick with a “good Chimney” on each end, the floors to be “good oak or ash plank,” the doors and window shutters to be “yellow poplar,” and all doors, window casings and sashes to be covered with three coats of white paint. Additional public structures planned for the town were a warehouse and a stray pen.

The court appointed commissioners to complete other municipal tasks: letting a contract to build a jail, and viewing and marking out a network of roads to connect Brownsville with neighboring settlements. Also appointed to calm ever-present fears of rebellion were slave patrols consisting of a captain and assistants who were to patrol twelve hours per month within five miles of the town south of Green River, “visiting all negroes quarters and suspected places of unlawfull assemblies of slaves.”

Other matters of public order addressed by the court included granting licenses to perform marriages, to practice law in the county, to keep a tavern (at specified rates for food, whiskey, lodging, and stabling horses) and to operate a ferry; one John Rhodes was doubly lucky to be granted a license to “retail spirits at his ferry.”

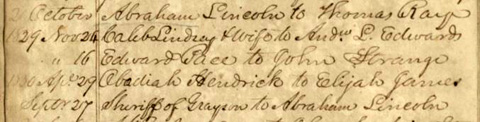

A finding aid and full-text scan of the Edmonson County Court order book can be accessed here. This collection also features militia rolls, fee books, data on early school districts, and land records, including a memorial book of early recorded deeds. The first page lists two deeds from 1830 (1829?), for 100 and 1000 acres respectively, from “Abraham Lincoln” to Thomas Ray, and to Abraham Lincoln from the Grayson County sheriff. Is this the Abraham Lincoln? More likely, it is the 16th president’s cousin and namesake, the son of his uncle Mordecai Lincoln who settled in Grayson County about 1811 and departed for Illinois about 1829.

For more collections of our county records, search TopSCHOLAR and KenCat.